Ah, the IFS costings are out. Quite long, but interesting.

EMBARGOED until 09.00am, 26 May 2017

Opening remarks on 2017 manifestos

Carl Emmerson, Deputy Director, Institute for Fiscal Studies

26/05/2017

You don’t need the IFS to tell you that there are big fiscal differences between the Labour and Conservative manifestos. Labour would raise spending to its highest level since the mid-1980s and tax to record levels in peacetime. The Conservatives would preside over yet more spending cuts alongside a modest increase in the tax burden. Labour have said they would increase capital spending dramatically and would accept a much bigger budget deficit than would the Conservatives.

That’s the big story. And actually that seems to be close to what each wants you to hear. But as ever there is rather more to it than that.

What Labour actually want you to hear is that the spending increases they promise, pretty much across the board, on higher education, childcare, schools, health, welfare, and the rest, would be funded by tax increases solely affecting the rich and companies. This would not happen. They have supposedly identified £49 billion of tax increases. That is an overestimate. They certainly shouldn’t plan on their stated tax increases raising more than £40 billion in the short run, and more likely than not they would raise less than that. They would certainly raise considerably less in the longer term. And the big increases in corporate taxes that they propose would still make a broad group of people worse off just as surely as would increases in VAT or in the standard rates of income tax – as the Liberal Democrats propose. When businesses pay tax, they are handing over money that would otherwise have ended up with people, and not only rich ones. Millions with pension funds are effectively shareholders. In the longer term, much of the cost is likely to be passed to workers through lower wages or consumers through higher prices. This isn’t to say we shouldn’t tax businesses. But we shouldn’t pretend that it is somehow victimless and hence fundamentally different from personal taxation. The impacts on households are just less transparent.

What Labour would do in the event that revenues did not come in as planned is unclear – would they raise other taxes, spend less or borrow more?

There is a case to be made for a bigger state. Labour’s proposals would not take tax and spending to unusually high levels among advanced economies: around Canadian rather than Scandinavian levels. But the case needs to be made with honesty about what it would mean for tax payments, not by pretending that everything can be paid for by “someone else”. If they were to embark on this set of spending increases some increase in taxes other than those mentioned in the manifesto looks likely. A state of the size the Labour party would likely would require broad based tax increases.

The Conservative manifesto by contrast appears to be selling a “steady as she goes” prospectus. But that does not mean no change from today because the Conservatives in government have already laid down big policy plans. It means big cuts in welfare spending. It means another parliament of austerity for the public services, including an incredibly challenging period for the NHS and real cuts to per pupil funding in schools. It is not clear that this would be deliverable. Barely two months after the 2015 general election they announced spending plans that were less tight than set out in their manifesto. Maybe they would do that again. I would also not bet against a Conservative government finding some additional tax raising measures.

Long term challenges

A surge in investment spending, as proposed by Labour, should, if well spent, have positive long term economic returns. Given that the Conservative government had in any case committed to some quite significant increases in investment spending, ramping up much more quickly does risk waste. On the other side of the ledger big increases in corporation taxes risk significant falls in private sector investment. This might compound the risks to investment associated with Brexit. Labour also propose a minimum wage set at a higher level relative to median earnings than in any comparable country other than France and at such a high level it would set the pay of more than a quarter of all private sector workers, and 60% of those under age 25. The latter element in particular looks like it could have the potential for imposing significant social and economic costs, risking the employment opportunities of many young people. We simply don’t know beyond what level a higher minimum wage would start having serious impacts on employment. It follows that sudden, large increases represent a gamble.

The Conservatives meanwhile propose a more modest, though still substantial increase in the minimum wage – and, like Labour, are abandoning the old model whereby the minimum was incrementally increased whilst an independent expert body meticulously checked at each stage whether it was having harmful effects on employment.

Their continued focus on reducing immigration would, if effective, cause considerable economic damage as well as creating an additional problem for the public finances. The OBR has already downgraded its forecasts for receipts by £6 billion in 2020–21 – and rising thereafter – due to lower expected net immigration. Meeting the Conservatives’ commitment to reduce immigration to the tens of thousands would hit tax revenues by a similar amount again.

EMBARGOED until 09.00am, 26 May 2017

That additional public finance challenge is especially pertinent in the context of an ageing population which will push up spending pressures on health, pensions and social care over the coming decades. On fairly conservative estimates these pressures could exceed 5% of national income, or £100 billion in current terms, by the middle of the century. Denying entry to young, working immigrants would make that challenge all the harder to meet. But so would continuing with the triple lock on the state pension, as Labour propose, or the similar double lock, as the Conservatives propose.

Arguably the Conservatives are at least attempting a nod towards dealing with the costs of ageing with means-testing of winter fuel allowances alongside this tweak to the triple lock. But in practice these would make a wholly trivial difference to spending.

Their proposals on social care have been in, shall we say, flux. The original proposals would have been more generous to those in residential care and less generous to those receiving care at home. It now looks like a cap on costs will be introduced, presumably increasing public spending overall. Surely a Green Paper, followed by a consultation – as the Chancellor announced in the March Budget – would be a better way to make policy then Monday’s U-turn on the proposed change in direction that was announced the previous Thursday.

Labour, by contrast, would do nothing at all to limit spending on pensioner benefits. Not only would they keep the triple lock and all the current benefits, they have even suggested fixing the state pension age at 66 rather than increasing in line with rising longevity. Male life expectancy at 65 has risen from 13 years to 18 years – that’s a 40% increase – since the start of the 1980s. It will rise further. Failing to increase the state pension age would increase spending by more than £30 billion a year by the middle of the century relative to current plans. It is hard to see the merit in such a proposition.

One of the striking things about Labour’s spending commitments is the extent to which they extend the writ of public provision rather than focussing on reversing cuts

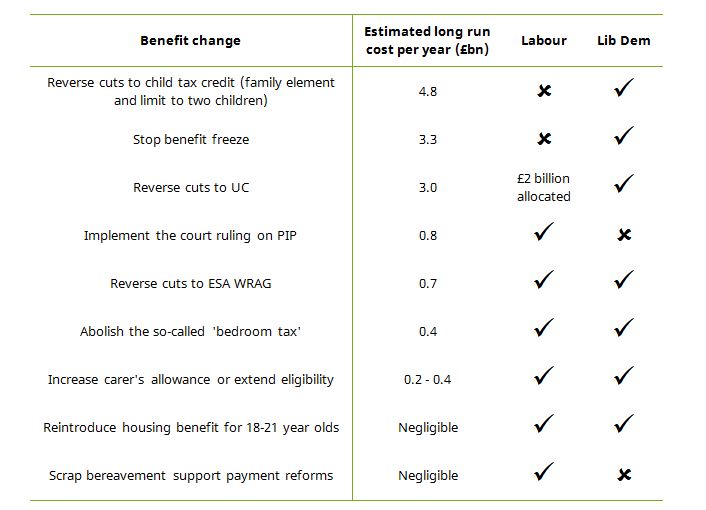

Taking the manifesto at face value the vast majority of the proposed cuts to working age benefits would stand. This is in sharp contrast with the Liberal Democrat manifesto. Labour’s proposed increases in health funding are modest. Spending would rise at barely half its long term average rate following the tightest seven years in history. Many of the deep cuts seen elswehere would, it would seem, remain.

The two big additional areas of spending are on childcare and on Higher Education. The former is costed by Labour at over £5 billion a year, a 70% increase on current spending levels. This is almost certainly an underestimate of the long term cost. That said their proposals would sweep away a complex array of subsidies in favour of relatively straightforward universal provision. This would arguably be the logical conclusion of a long term journey by the state.

Proposals to make HE free would instead be a reversal of policy pursued by all governments in the last two decades. Abolishing tuition fees for HE is the most expensive pledge in the Labour manifesto and is a policy which benefits most the most successful of the generally better off section of the population which attends university. It might also constrain growth in the higher education sector as expanding the number of places available would become much more expensive for government.

From the Conservatives we have little or nothing: compared to a typical Budget their manifesto is extremely light on tax and spending proposals. The promised £8 billion increase in NHS funding is essentially consistent with the March Budget: as planned over the next few years and then stable a share of national income after that. Given the scale of pressure the NHS is already under there must be serious doubts as to the deliverability of such a tight spending plan.

As with the NHS Labour promises more on schools than do the Conservatives who promise little more than that implied by the March Budget.

The big question regarding the deliverability of Conservative spending plans is well illustrated by choices over public sector pay. Continuing with a 1% cap would take pay levels in the public sector to easily their lowest relative to the private sector in recent decades, with problems of recruitment, retention and morale possible outcomes. Labour’s plans, by contrast, imply public sector employers facing a £9 billion a year increase in employment costs.

Public finances

Even taking an optimistic view on tax receipts Labour would run a substantially bigger deficit than the Conservatives – to the tune of £37 billion more in 2021–22 on our calculations. That number should be taken as purely illustrative given all the uncertainties involved, both over policy and the economy. It rather optimistically assumes Labour’s measures would raise £41 billion extra in tax. At total borrowing of around £58 billion, that would still leave Labour with plenty of headroom against their target of balance on the current budget.

They might find it harder to meet their second target of getting debt down as a fraction of national income. If it falls it won’t fall by much. With debt approaching 90% of national income there may be some risk with a set of policies which do not result in its level turning decisively downwards.

For the Conservatives the aim of overall budget balance remains, but not until the mid-2020s – beyond the end of the coming parliament. That provides flexibility relative to an earlier date, but remains a much tighter ambition than Labour’s. On manifesto plans the deficit could still be around 1% of national income by 2021–22, or around £21 billion, leading potentially to a fourth parliament of austerity after that.

Conclusion

The shame of the two big parties’ manifestos is that neither sets out an honest set of choices. Neither addresses the long term challenges we face. For Labour we can have pretty much everything – free HE, free childcare, more spending on pay, health, infrastructure. And the pretence is that can all be funded by faceless corporations and “the rich”. There is a choice we can make as a country to have a bigger state. That would not make us unusual in international terms. But that comes at a cost in higher taxes which would inevitably need to be borne by large numbers of us. Labour are not merely asking for a bit more from the top 5% whilst leaving “ordinary households” alone. There is no way that the tens of billions of pounds of tax rises they promise would be borne entirely by such a small group. If only policy-making were that easy.

EMBARGOED until 09.00am, 26 May 2017

The Conservatives simply offer the cuts already promised. Additional funding pledges for the NHS and schools are just confirming that spending would rise in a way broadly consistent with the March Budget. Compared with Labour they are offering a relatively smaller state and consequently lower taxes. With that offer come unacknowledged risks to the quality of public services, and tough choices over spending. The difficulty in making some of those choices has been well exemplified by the to-ing and fro-ing, to put it politely, over the funding of social care.

The Labour manifesto comes with two big risks. The first is that they might well not raise anything like the tax revenues they want from their proposed measures. The second is that some of the proposed tax increases, alongside the very big increase in the minimum wage, and other labour market regulation, would turn out to be economically damaging. For the Conservatives the big risk is that, after seven years of austerity, they would not be able to deliver the promised spending cuts either at all or at least without serious damage to the quality of public services. Their tight immigration targets would, if delivered, also damage the economy and the tax base.