Rado_N

Yaaas Broncos!

Yea she's essentially the US Katie Hopkins, only dialed up to 12 in typical US fashion.She's a massive troll. Moreso a performer than an analyst, who generates click bait to sell her various books.

She's a horrible person.

Yea she's essentially the US Katie Hopkins, only dialed up to 12 in typical US fashion.She's a massive troll. Moreso a performer than an analyst, who generates click bait to sell her various books.

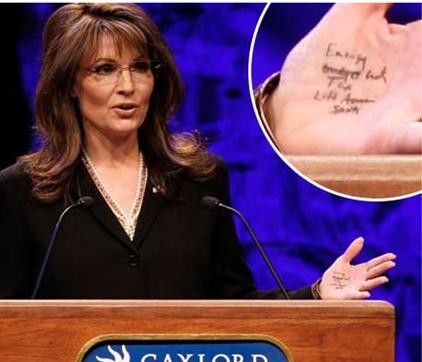

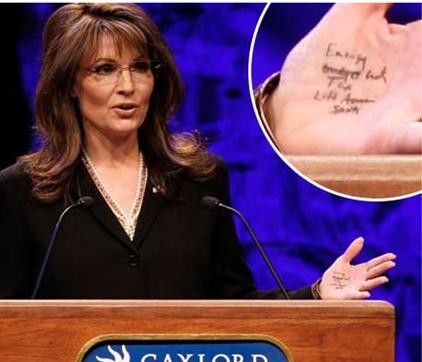

Honestly who writes the speeches for Sarah Palin?

Shea a truly vile hateful wench.

Honestly who writes the speeches for Sarah Palin? I think even a 3rd grader could write more coherent speeches than what she does.

FixedShe usually wings it, always has. Her style isn't well suited for teleprompters anyway since her audience (or at least those who like listening to her) prefer nonsense speeches.

She usually wings it, always has.

She usually wings it, always has. Her style isn't well suited for teleprompters anyway since her audience (or at least those who like listening to her) prefer non scripted speeches.

Unsurprisingly, Wlezien and Erikson found that as the campaign goes on, the polls start looking more like the eventual outcome.

But they also found that the rate of this improvement isn't linear. There are some volatile periods of the campaign in which the polls' predictive value surges quite quickly. And there are other, more stagnant periods in which the polls might change, but those changes don't tend to have any lasting impact.

One of those volatile and consequential phases is the one we're in right now. The authors found that around 300 days before the election (mid-January), general election polls are essentially meaningless — their predictive value is close to zero. But by the time we get to mid-April of the election year, polls explain about half the variance in the eventual vote split. And mid-April polls have correctly "called" the winner in about two-thirds of the cases since 1952.

So stealing guests credit card info makes what point? Other than perhaps to show they can, but at this point we all pretty much know data breaches can happen.Trump's Hotels just got hit with a massive data breach. Probably anonymous trying to make a point.

Does it have a pulse?but you would still do her?

She usually wings it, always has. Her style isn't well suited for teleprompters anyway since her audience (or at least those who like listening to her) prefer non scripted speeches.

Trump's Hotels just got hit with a massive data breach. Probably anonymous trying to make a point.

Trump seems to have the emotional range of a Power Rangers villain and the social skills of a teenage Minotaur. He looks like a pumpkin having a nervous breakdown, talks like the words are being fired out of his mouth by a tennis ball launcher and has the general manner of an arrogant televangelist suspected of murder by Columbo.

With almost infinite resources, the closest the Republicans have got to producing a popular candidate is Ted Cruz: a cross between a permanently disappointed sitcom vampire and the high school yearbook photo of every serial killer of the modern era.

Serves them right for staying at his hotels and funding his stupidity.So stealing guests credit card info makes what point? Other than perhaps to show they can, but at this point we all pretty much know data breaches can happen.

Shitty for the people who have to deal with their information being stolen

I think Trump is an absolute retard, but Anonymous is even worse.

How many times have they declared war on ISIS now? It's a bunch of fat neck beard reddit life failures sitting around circle jerking each other off with stupid hats and stupid masks pretending they are relevant other than as a joke.

Her speeches are plenty scripted

Exercising

D̶e̶v̶e̶l̶o̶p̶e̶r̶ NOT

Tax

Lift Aquaman

Sorry

Isn't there a rule where you can't be eligible for the nomination unless you have won a minimum of 8 states? I'm sure I heard that on CNN or FOX recently. Or is just winning delegates in 8 states?

Last I heard it was created back in 2008 (I think) to keep that cretin Ron Paul and his conspiratard supporters out of the GE.

Just watched Reagan / Bush 1980 debate. They sound like Democrats compared to todays Republicans.

Reagan even said about illegal immigration from Mexico " why build walls when we should have workers come in- work- pay taxes- and go back and forth over the border as they please"

Unbelievable difference to Trump.

but you would still do her?

who the feck is Roger Stone?

The new, surprisingly-reported-in-some-realish-news-sources rumor is that Cruz is in the black book of a dead DC madam.

Excellent.https://mobile.twitter.com/SteveKornacki

some tidbits from early exit polls. A good night for Bernie looking at the numbers. Probably a 55-45 split

With the standard safety warning that Bernie won Missouri and Illinois per the early exits, so could change by a few % either way yet.https://mobile.twitter.com/SteveKornacki

some tidbits from early exit polls. A good night for Bernie looking at the numbers. Probably a 55-45 split

With the standard safety warning that Bernie won Missouri and Illinois per the early exits, so could change by a few % either way yet.