Dobba

Full Member

Poor Cenk Tosun's efforts, for the Erdogan propaganda machine, have been glossed over by everybody.

I'm curious to know your line of reasoning here. Do you really think he'd help Pakistan move forward in the right direction?Good luck to Erdogran. I like the bloke. Would gladly have him in Pakistan.

I'm curious to know your line of reasoning here. Do you really think he'd help Pakistan move forward in the right direction?

You don't know the beginning of how backwards our country is. At least this guy bought jobs, industry, energy, has a notion of statesmanship (even if it is just arrogance). Currently we have dictators who are voted in every 5 years.

It might have been a good argument years ago, but he doesn't even have the economy anymore. He's been gradually gutting the country for some time now, selling off everything and closing down businesses at the expense of foreign firms. He was also dumb enough to ostracize the people who originally made Turkey's economy successful, which is probably why the former is happening.

In terms of being a despot, I think he'd be in his element in Pakistan as much as any of what you've already had. The only reason he isn't quite there in Turkey now is because he's still trying to overcome a few more obstacles (Atatürk's legacy, for example) in order to be just that.

If Turkey sticks with him long term, it's proper fecked. If it manages to get rid soon, it will still be a slow rebuilding process.

Anyone who is pro-islam is slated in the western press

Erdogan was lionized in the Western press for years until the 2013 protests and the Syrian conflict.

Is the economy in Turkey bad? As a tourist you don't really understand anything in detail.

I've always thought of Erdogan as someone who's been Pro-Turkey, our political class are anti Pakistan and pro-corruption. I don't know much about the internal politics of Turkey, the reporting in the Pakistani media is usually about the positive stuff like investment and charity work, and I don't really trust much of what I read in the western media. Anyone who is pro-islam is slated in the western press.

There is serious support for Erdogan in Germany, but I'm very suspicious about both claims. I think there's a lot of gut feeling involved in these discourses. I'll try to point out my issues with the first one (Erdogan support).Most of Turkish German people seem to support him, and a lot of them aren't really integrated in Germany (generally stay only with other Turkish people).

Interestingly, those who have left for Germany late in their lives (study, job) seem to be anti-Erdogan. At least those I know.

Fair enough, I said these are only flashlights and there may well be contradicting arguments. A (purely speculative) counter-argument might be that those who feel strongly about Erdogan (positively or negatively) were likelier to participate, and the ones who didn't may be less interested on average. Do you perhaps have data on those who didn't vote, or political opinions in general?In Germany the percentage of AKP vote in 2015 and the share that supported the referendum in 2017 have been higher than in Turkey itself. Naturally the voter turnout% is always going to be lower for people who are living abroad. I havnt looked it up en detail but usually countries struggle to mobilze more than 30% of those who are eligible to vote, while living abroad. In various cases the turnout ends up in single digits. Its not entirely convincing to use the turnout as part of an argument against the popularity of Erdogan. On average, Turkish citizens, who live in Germany are more pro Erdogan than Turkish citizens in Turkey. There is no gut feeling involed.

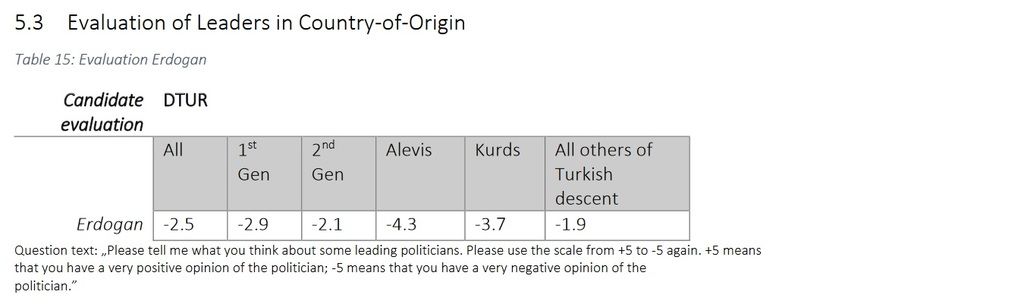

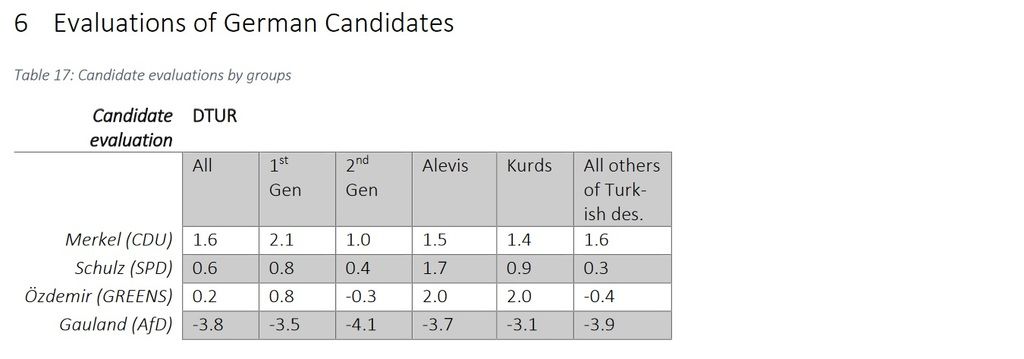

Even when factoring out Kurds and Alevites, the approval rate is still -1.9 (on a -5 to +5 scale). But I admittedly can't say much about the survey's methods and general validity.So Merkel scored an average of +1.6 while Erdogan landed at -2.5, way worse than all German politicians listed bar Gauland.

Fair enough, I said these are only flashlights and there may well be contradicting arguments. A (purely speculative) counter-argument might be that those who feel strongly about Erdogan (positively or negatively) were likelier to participate, and the one's who didn't may be less interested on average. Do you perhaps have data on those who didn't vote, or political opinions in general?

To be clear: the post I quoted stated most Turkish-Germans seem to support Erdogan. To me, that suggests approval rates of ~60-70% upwards (if we're not nitpicking, 51% would be "half" rather than "most"). That's the popular narrative I referred to, and I said in the light of some of what I've seen, this claim deserves more scrutiny. If then the result is really that bad, fine (or rather: shit). But my point was it has to be supported instead of just taken for granted without further ado, as it often is.

What would you say about this?

Even when factoring out Kurds and Alevites, the approval rate is still -1.9 (on a -5 to +5 scale). But I admittedly can't say much about the survey's methods and general validity.

(This one: https://www.researchgate.net/profil...ion-Study-IMGES.pdf?origin=publication_detail )

Zusammengefasst hat also knapp die Hälfte der Türkeistämmigen Heimatgefühle für Deutschland. Dagegen sehen 47 Prozent nur die Türkei als ihre Heimat; vier Prozent fühlen sich nirgends zu Hause. Betrachtet man die heimatliche Verbundenheit im Zeitverlauf, so wird deutlich, dass diese offenbar von allgemeinen Stimmungen beeinflusst wird. Insbesondere seit 2012 nimmt die Verbundenheit mit der Türkei zu; hingegen nimmt die Verbundenheit mit Deutschland tendenziell eher ab beziehungsweise stagniert. Diese Entwicklung lässt sich zum einen möglicherweise damit erklären, dass die AKP seit einigen Jahren deutlich stärker um die Gunst der "Auslandstürken" buhlt und sie in ihre politischen und strategischen Überlegungen einbezieht – etwa durch die Gründung eines Ministeriums für die Belange der "Auslandstürken", durch die Schaffung von Wahlmöglichkeiten in den Konsulaten oder durch symbolische Identitätsangebote durch türkische Politiker als "stolze Erben" des Osmanischen Reiches. Zum anderen wirkt die gleichzeitige Fokussierung der deutschen Integrationspolitik auf die angeblich gescheiterte türkische beziehungsweise islamische Integration als Identifikationsbarriere.

Connection was that those strongly influenced by Erdogan/AKP are (probably) likelier to vote, therefore may make up a higher percentage among the voters than among the non-voters. But, as I said, that was only speculative reasoning.Those who feel strongly about Erdogan (or politics in general) are more likely to participate in elections. I dont think thats controversial to say, but I don't see the connection to your argument.

So I get your argument is that the overall turnout (in a diaspora referendum) is a strong indicator of the political leanings of those who didn't vote themselves, at least under these specific circumstances (strong nationalism, AKP campaign, etc.) Never thought of it that way, and it still doesn't seem very conclusive to me at first sight. But I take that with me as a possible interpretation, perhaps it grows on me.A high turnout in combination with a high share of pro Erdogan votes indicates in my opinion that Erdogan is a) pretty popular in Germany and b) also very good at mobilizing voters.

German-only nationals (the majority of Germans of Turkish descent) don't appear in the referendum data*, so imo it needs quite a bit of extrapolation to draw conclusions on them from that. The results I posted on Erdogan's image among this demographic are at least a hint regarding the question of his popularity in that specific group.I have no idea about this study, but its difficult to measure popularity. Additionally I don't think one can simply put Turkish and German politicians on the same scale (the study didn't do it). It would be interesting to see how other Turkish politicans are seen. That said this is a very weak data point compared to the election data.

The facts about voting results and turnout are of course undeniable and also bear some further-reaching implications. A reason for the semantics-heavy discussion may be that I primarily referred to a particular qualitative statement throughout the exchange ("most Turkish Germans..."), while your angle seems to have been more general. That probably leads to a bit of labouring on meanings and interpretations.My thoughts on this are far simpler and less sophisticated. I don't know much about the political leanings of those who didn't vote. A general observation is that diaspora turnouts are on average a lot lower than those at home. I think most of our discussion is actually about semantics and not about the content.

I agreed on that, but still think it can be read without the comparison aspect as well:About the study: I don't think that it is useful to compare the popularity of Turkish politicans and German politicans with such a methodology.

Point taken on the difficulties of comparing Turkish with German politicians, but Erdogan's approval score as such is still low (2,5/10 overall; 3,1/10 without Kurds/Alevites). Assumed the survey isn't total nonsense, that must at least be explained.

While that may be somewhat true for some few cities it isn't for the vast majority of Germany, the Turkish Germans make up a large portion of companies like Daimler, BMW or Siemens workforce and are generally well integrated in cities like Stuttgart or Munich. I have lived in two German cities where I had a substantial amount of neighbors with Turkish heritage, and to describe it as anything but a peaceful coexistence is ignorant. They speak German, work in German companies and their children attend state schools, what are they if not integrated?Most of Turkish German people seem to support him, and a lot of them aren't really integrated in Germany (generally stay only with other Turkish people).

99 years today sine Ataturk arrived in Samsun to kick-start the Turkish resistance:

Back in May 2014, 1 Euro could buy 2.88 Liras. Today, 1 Euro can buy 5.28 Liras.

I love this guy. He wanted Turks to move on after his death and not worship him, but he's long been the ultimate obstacle that has kept that dictator awake at night. A true leader, unlike all of the unaccountable thieves of today.

Currently at 5.70 and climbing. I said in another thread that my grasp of economics is terrible, but I know this isn't good. This is horrible. He's leading the country over the edge at an alarming pace, and yet there's still a very realistic chance that he'll just go and steal the election.

Yeah, but having every printed money with his face was the most hilarious thing I have ever seen.

Started out as a teacher from a working class background, entered parliament at 38, CHP MP for small city near Istanbul called Yalova (currently in his fourth term). Twice tried to become CHP chairman but was beaten by Kılıçdaroğlu on both occasions.

His political career thus far has been defined by his very vocal opposition to AKP polices e.g. removing immunity for parliament members, which Kılıçdaroğlu supported and saw Selahattin Demirtaş placed in prison.

His popularity stems from him being a legitimate contender i.e. he's charismatic and intelligent enough to beat them to the punch, which has taken Turks aback because it's practically been unheard of since the AKP came to power.

His proposals include reducing the threshold a party requires take its place in parliament from 10% to 5% (significant, as Kurdish people with the HDP won't be screwed, and it opens the door for other, smaller parties), changing anti-terror laws (somewhat ambiguous when read like that, but safe to say a change in direction from everyone being labelled a terrorist like happens in Turkey today), and free education (obviously a topic he's passionate about since he was said to be a good teacher).

How is he religion wise? Secular like Turkey should be, or a loon like Erdogan?

Wow, that’s an insane crowd.Thanks. Awesome picture from his Twitter account.

Crazy how that road on the left is also full of people who wanted to get closer.

Wow, that’s an insane crowd.

Does he have a fair chance in the election?

As secular as they come. Actually, those far things I probably should have mentioned. He's pretty much the embodiment of Kemalism, and the free education he's proposing is secular. Somewhat amusing story on that front - he was "caught" drinking beer on a beach during Ramadan, but he noticed the camera and carried on drinking. That's what the AKP can't come to terms with - all the mud they're slinging won't stick because he owns everything about himself e.g. he wrote some romantic poems in the past, but he just laughed it off and made a reference to somebody in the conservative AKP having bought a cock ring.

At the same time, his mother and sister wear the headscarf, so the AKP are finding it difficult to even drive home the "but he's oppressing our us and our religion" angle.