Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced on Thursday that an Egyptian mission under the supervision of Egyptologist Dr. Zahi Hawass discovered a city – dubbed the Rise of Aten – which had been under the sands for 3,000 years, dating back to the reign of Amenhotep III. The statement, which was shared on the Ministry’s social media pages, adds that “the largest city ever found in Egypt” was founded by one of the greatest rulers of Egypt, namely of the New Kingdom, Amenhotep III. The latter had been the ninth king of Dynasty 18, ruling Egypt from 1391 till 1353 B.C.

“Many foreign missions searched for this city and never found it. We began our work searching for the mortuary temple of Tutankhamun because the temples of both Horemheb and Ay were found in this area,” Hawass said. “The city’s streets are flanked by houses, which some of their walls reach 3 meters high. We can reveal that the city extends to the west, all the way to the famous Deir el-Medina.” Betsy Brian, Professor of Egyptology at John Hopkins University in Baltimore USA, described the discovery as “the second most important archeological discovery since the tomb of Tutankhamun.”

Brian continued to add that it “will not only will give us a rare glimpse into the life of the ancient Egyptians at the time, but will help us shed light on one of history’s greatest mystery: why did Akhenaten and Nefertiti decide to move to Amarna.”

The city is considered a vital clue to the cultural and religious developments of the reign of Amenhotep III whose succession would come at the hands of his son, Akhenaten. The latter’s ambitions had resulted in a move from the capital of Thebes to a newly-built capital near contemporary Minya, Tel-El-Amarna. Due to organic material from which settlements were constructed from, their survival rates into modern day Egypt is rare. As such, along with the famed settlement of Deir-El Medina, the city’s discovery can provide archaeologists with a glimpse of daily life activities in ancient times.

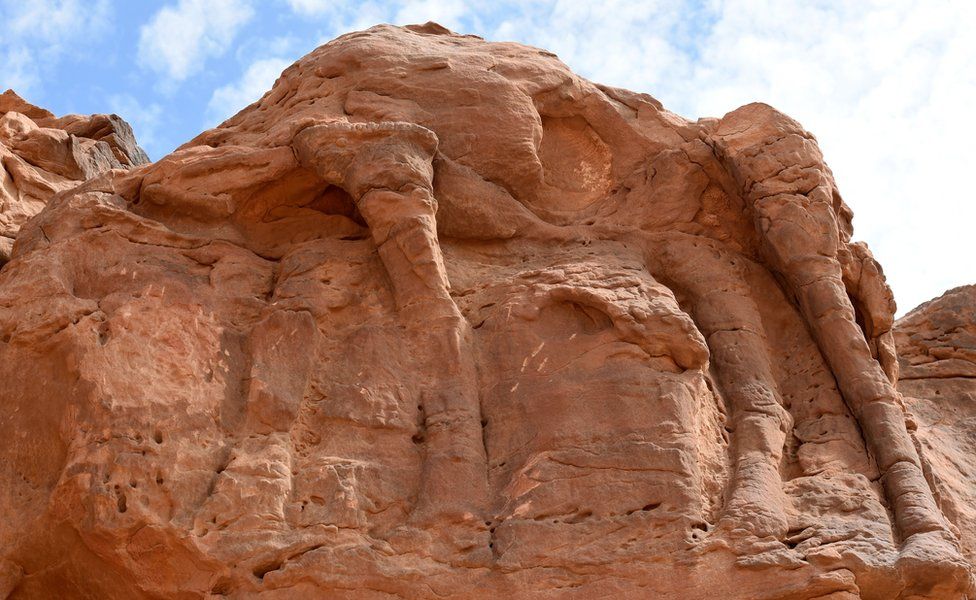

After Hawass’ team began excavating in September 2020, several areas and neighborhoods were uncovered, such as the administrative and industrial center and a bakery. The statement adds that the city is in good condition of preservation, with almost complete walls and rooms filled with tools of daily life. The discovery comes after Egypt’s

historic pharaohs’ golden parade, which saw 22 mummies transported from the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square to their new home, the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, in a glittering display. Among the mummies was the body of Amenhotep III.

Earlier in January 2021, Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities announced new

‘major’ discoveries at Saqqara archaeological site, which included a new trove of treasures and an ancient funerary temple, dating back to the New Kingdom. Announcements of discoveries highlighting Egypt’s ancient history are significant as they provide a natural boost to the country’s tourism sector. The tourism sector represents the main source of foreign currency income in the country in addition to being an important building block to stabilizing Egypt’s economy.

They simulated what sea levels were like when Homo Erectus made this journey. And it wasn’t just a superstar swimmer or one guy floating away on a log after a typhoon; they raised families there. And Doggerland wasn’t just an island.

They simulated what sea levels were like when Homo Erectus made this journey. And it wasn’t just a superstar swimmer or one guy floating away on a log after a typhoon; they raised families there. And Doggerland wasn’t just an island.