With five minutes of the 1986 World Cup semi-final remaining and

Argentina leading Belgium 2-0, Ricardo Bochini came on for Jorge Burruchaga. He was 32, and had been omitted from the squads in both 1978 and 1982. This time, though, Diego Maradona had demanded that he be picked. Those five minutes plus stoppage time would be the only World Cup football Bochini ever played. As he trotted on, Maradona ran over and shook his hand. "Maestro," he said, "we've been waiting for you."

On Saturday Bochini, Maradona's idol and still the great hero of Independiente, turns 60. He is, frankly, the most unlikely of heroes, described by the columnist Hugo Asch as "a midget, ungainly, imperturbable, without a powerful shot, nor header, nor charisma". Yet it was just that sense of improbability that marked him out for popularity: in his overt ordinariness he embodied the imaginative genius of Argentinian football, the kid from the streets who made good not by any advantage of upbringing or physique but through his untutored technical ability.

It is this, the anthropologist Eduardo Archetti has claimed, that is characteristic of the Argentinian game, which was set up, for various economic, cultural and historical reasons, in opposition to the British game; where the British game was learned – taught in the schools, and reliant on the physicality that came from good diet – the Argentinian game was wild, spontaneous, based in streetwiseness and learned in the

potreros, the increasingly rare vacant lots on the back streets of Buenos Aires.

Bochini doesn't like interviews. I'd tried and failed to meet him before, but last time I was in Buenos Aires, researching a book on the history of Argentinian football that should come out later this year, he finally agreed to meet, telling me to wait for him at a particular street corner in Palermo at 9.30pm. By 9.50 he hadn't showed. I called him but there was no answer. I was on the verge of giving up – and I was flying back to London the following day – when, just before 10, he rang and gave me an address a couple of blocks away. Two minutes later he was answering the door.

Although he lives in one of Buenos Aires' wealthier neighbourhoods, Bochini has a strangely ordinary flat for one so feted. The front door opened on to a sparsely decorated main room: at one end a small sofa and two chairs clustered around a television that was showing a Copa Sudamericana match, while at the other was a dining table on which lay some half-done schoolwork.

Bochini sat awkwardly on the sofa, dwarfed by the large padded coat he kept on throughout the interview. In his right hand he cradled his car keys, as though at any time he might decide enough was enough and make a break for it. He spoke throughout in a dry monotone: he wasn't impatient, exactly, nor was he impolite, and he clearly gave his answers significant thought, but equally his relief was obvious when we'd finished. He was, I think, just extremely shy, his discomfort hard to believe in somebody who had been so wonderfully instinctive as a player.

Bochini was born in Zárate, around 60 miles north of Buenos Aires, which meant that when Independiente took him on he had to make a journey of five hours, using three buses and a train, just to get to training. He had been a San Lorenzo fan as a child, and had dreamed of playing like José Sanfilippo, their combustible and prolific centre-forward, but his lack of pace and height soon made him revise his plans. "I played some games as a No9," he said, "but my body was better for a No10, because the centre-forward was usually bigger, taller and stronger."

Fans who had seen him in the youth team and the reserves demanded that Bochini be selected for the first team and, by the end of 1973, he had begun to establish himself in Humberto Maschio's side, helping them defend the Libertadores title they had won the previous season.

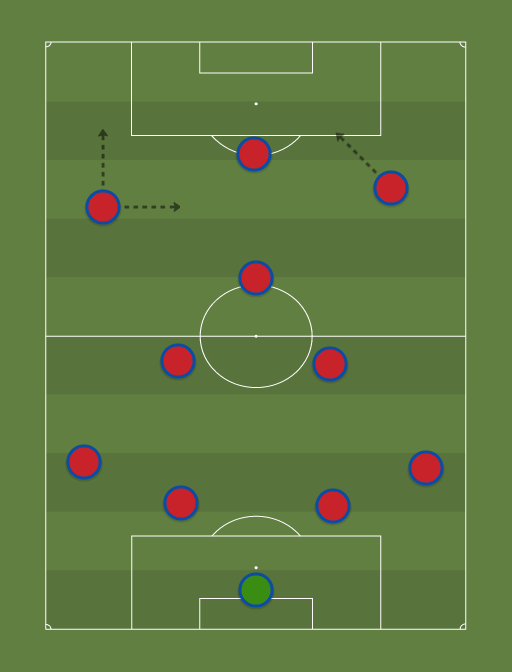

Then, in Rome for the Intercontinental Cup final against Juventus – played that season over one leg only – came the consecration. Independiente had been under pressure for most of the game and Juve had missed a penalty, but with 10 minutes remaining Daniel Bertoni broke from halfway and nudged a pass to Bochini, who received it on the half-turn, skipping by Claudio Gentile, before advancing and playing a one-two with Bertoni, then scooping the ball over Dino Zoff. It wasn't just the winner and a goal that sealed his place in Independiente legend, but it encapsulated the astonishing partnership he had with Bertoni, a powerful, quick winger who was always looking to cut in from the flank.

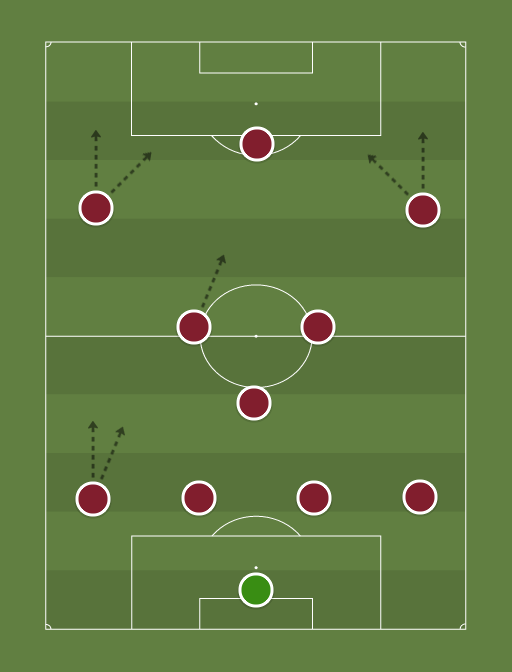

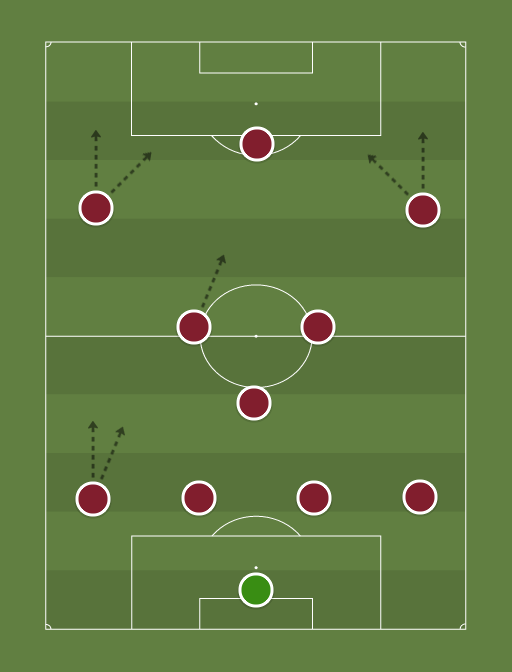

"With Bertoni we understood each other from the very first time we played together, and we didn't have to speak about it," Bochini said. "It was just natural; it really felt as though we had been playing together for our whole lives, based on our personal attributes: I was quick and skilful, he was powerful and good for one-twos, what we call la pared [wall pass] in Argentina. He could play in different positions but I always wanted him to be close, because we understood each other so well with those short passes."

Bochini became a master of that most revered moment in Argentinian football,

la pausa, the moment when a No10, poised to deliver a pass, delays a fraction, waiting for the player he is looking to feed to reach the ideal position (it's a skill at which Juan Román Riquelme excels but the most famous example, gallingly for Argentinians, is probably by a Brazilian, Pelé waiting for Carlos Alberto's overlap before laying the ball off for him

to score Brazil's fourth in the 1970 World Cup final).

His explanation of the skill suggests an extraordinary football intelligence, the ability to visualise and predict the behaviour of others that recalls the evolutionary biologist Stephen J Gould's assertion that most top sportsmen have a capacity to make rapid calculations that would see them hailed as geniuses in almost any other field.

"The way I see it," Bochini said, "there are two types of

pausa, or two ways of doing

la pausa: with the ball going slowly or with the ball travelling fast. Sometimes you have to go fast, carrying the ball with you, to wait for another player to come into position. It happened for example in a game against Olimpia de Paraguay [in the Libertadores group stage in 1984], [Alejandro] Barberón gave me the ball and started running, and I had to go fast with the ball but I was also waiting for him. If I had stayed in my position, without moving, it wouldn't have been possible to assist him properly, so I had to run, with the ball, but knowing that I was waiting for him to come into the best position to give him the ball back.

I did, he crossed it and we scored.

"And another time, against Grêmio in Porto Alegre, I had the ball at my feet but I had to wait, because they were sitting back very well and there was nearly no space, so I had to hold the ball against a marker, knowing that I had to wait for Burruchaga, who had already started running to break the lines. We were close to the box, so there wasn't much space and it had to be a very sharp pass.

I waited, and then I gave him the pass, and we scored.

"This is the typical explanation of

la pausa, waiting for a team-mate by holding the ball. The first one, the pause in speed, is a total revelation, nobody knows about it [he emitted a brief and slightly unnerving chuckle] and nobody has done it. If I had stayed in midfield, he would have been 30m away and even if he'd managed to get the ball, nobody would have been in the box to get on the end of his cross and score, so I had to run fast, but waiting at the same time, because we were in midfield and therefore with plenty of space but plenty of metres to cover."

Bochini believes the capacity to understand movement in such a clinical way is innate. "None of this is something that you can teach," he said. "I believe it comes in the moment, it depends on the inspiration of your players. You have to know how to make

la pausa, and another has to know that while the team-mate is making

la pausa, he's also watching who's going to make the proper movement in order to surprise the opposition.

La pausa without a team-mate that collaborates is just holding the ball until, perhaps, you get fouled and waste some time, if you need to waste time.

"It's important to have players capable of fitting your purpose. If you don't have quick players, like Barberón or Burruchaga, who like to make vertical runs, then

la pausa is useless. But technique can and must be trained. I had my share from the

potreros, but during matches, I believe more in matches than training sessions, technique can improve because you face the real situations of the game, and you have to resolve them as quickly as possible, and therefore the more precision your foot has, the better it is for the team."

And Bochini, for all that he was slow and physically unprepossessing, was always precise. Maradona may have been waiting for Bochini in 1986, but for most of his career, the maestro was waiting for others.