THESE VIOLENT DELIGHTS: THE ROMANCE AND TRAGEDY OF BATISTUTA'S FIORENTINA

The rain thuds down on a murky February afternoon in Florence, blurring the tired limbs of the home side in purple, of Milan in their stripes of red and black. Beards drip; glossy Latin haircuts shed water like slate roofs into drainpipes.

Going into that fateful afternoon at the Stadio Artemi Franchi, Giovanni Trappatoni’s Fiorentina sit where they have done since the early days of the 1998-99 season – at the top of Serie A. Their lead over second-placed Lazio is three points – a sizeable gap, but no gulf – yet such has been La Viola’s dominance over the first half of the season, the title seems destined to return to Florence after a thirty year wait. A powerful Milan side – Maldini, Albertini, Bierhoff, Weah, Boban – are third.

Eighty-five minutes have gone by without either defence giving way. Milan force a corner and a final chance to break the deadlock.

Back when the two sides met in September, Fiorentina had laid down a marker with a crushing 3-1 victory on an equally wet afternoon at the San Siro. All three had come via the laces of Gabriel Batistuta’s right boot: a drive from the edge of the area flashed past Lehmann in the Milan goal; a Rui Costa through ball hammered in from a narrow angle; the third clinically smashed into the roof of the net from that deceptively tough situation, the indirect free kick from six yards out.

Now Batistuta is back defending the Milan set-piece. The Argentine finds the ball falling to his feet: he stretches to clear it.

Seconds later, he lies stricken on the sodden turf, clutching his knee. Anguished looks are cast around. Something is clearly wrong. Clearly the script is being misread. In one fateful moment – the sort that sticks in the memory in a slow, tragic motion, Florentine dreams mutate into fears. Batistuta, the fallen angel, is stretchered from the pitch. So begins the slide. Fiorentina’s lead is slowly, cruelly eaten away at. There is to be no

scudetto.

Batistuta arrived back in Italy that year on the back of a five-goal World Cup with Argentina, including a hattrick against Jamaica. Our first glimpse comes in mid-September, in a sun-drenched Florence: an opening-day strike against Empoli gets him up and running.

Batistuta is La Viola’s footballing spearhead and spiritual leader. To the fans, he is a demigod, not only for his goals, but also his decision to stick with Fiorentina after being relegated in 1993 – and then immediately take them to the Serie B title with a sixteen-goal haul. Even greater returns have followed since the return to Serie A. His hair is long, yet without any trace of effeminacy; it straggles over an upturned collar and a rugged chin of stubble. He is a leopard with the ball at his feet, moments of gracefulness culminating in carnivorous finishes, leaving his chosen prey – occasionally the centre-half, almost always the goalkeeper – helpless. His dead ball is appropriately lethal. The brutality of each goal is celebrated with the swivel of an imaginary sub-machine gun, or a jump and the pumping of a fist. This is joyous brutality.

Serie A soon gets used to the sight: by the time a twenty-five yard free kick is driven home with characteristic violence in a 3-0 drubbing of Vicenza on the last day of January, Batistuta has eighteen goals from nineteen games. Even Fiorentina’s disqualification from the UEFA Cup, after a fan takes the gun-totting celebrations too far and throws a bomb at a linesman during a tie with Grasshoppers Zurich, only seems to drive Batistuta on. He describes the decision to throw out Fiorentina as

‘like being thrown out for a crime you haven’t done.’

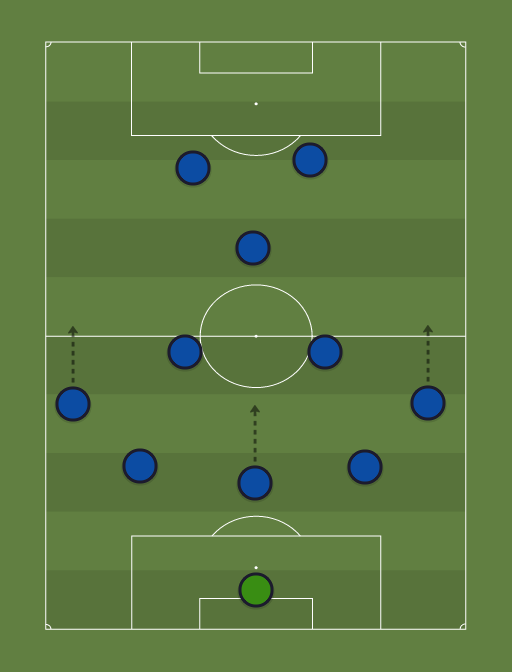

Not that Fiorentina are a one man team. Admittedly, the only real other outfield star is Rui Costa, who provides the through-balls unleashing Batistuta’s thunder, in front of a midfield spine built upon the labours of Sandro Cois, Guillermo Amor and Christian Amoruso. Mauricio Toricelli patrols the right-flank, the blond German Jorg Henrich the left. Between the posts, Francesco Toldo is as solid presence as any goalkeeper at the time; he will later be a genuine competitor to Gianluigi Buffon in the national team. Luis Oliveira and Edmundo chip in with goals, the latter at this point still famous for his on-pitch abilities rather than his future ability to intoxicate hired circus chimpanzees at his son’s birthday party. And there is La Viola itself: that deep purple, the colour of emperors. No-one else in Europe plays in purple.

Then there comes February and Milan. Like Samson shorn of his locks, without the injured Batistuta – out for a month – Fiorentina fall apart. His strike partner has fled the scene: Edmundo is partying at the Rio carnival; he misses three games in the process. The sidelined Batistuta is furious, his frustration is clear. Speaking to the press, he unleashes an extraordinary, prescient outburst at Edmundo, Trappatoni and the club’s owner, Vittorio Cecchi Gori. Even on crutches, Batistuta retains an air of the untouchable:

“Batistuta has exercised an act of justice,” gushes La Gazzetta dello Sport in biblical tones,

“acting as a leader, as a captain, an apostle of La Viola. He threw his crutches against treachery and his accusations spared no-one.”

Without their deity leading the line and with the ‘Animal’ back in Brazil, the goals dry up. Trappatoni shuffles his strikers with an increasing air of desperation: the spunky Anselmo Robbiati, the ineffective Carmine Esposito, the fading Oliveira. None can even dream of replacing Batigol. Fiorentina fall to defeat to Udinese and are held to a scoreless draw at home by Roma. A late Torricelli equaliser is required to rescue a point at lowly Salernitana.

By the time Batistuta returns to the starting eleven after a five-week absence, Fiorentina have been overhauled by Lazio and are just a point clear of third-placed Milan. All is not lost, however: just four points separate La Viola from the top – and the hit man is back.

But the momentum that fuelled the charge before February has evaporated. Now it is Fiorentina’s turn to suffer at the hands of brilliant Latin American forwards. In Venice, on the eve of the Ides of March, the on-loan Uruguayan playmaker Alvaro Recoba bends two free kicks past Toldo, and then – in stoppage-time – dances around him for a third: Venezia four, Fiorentina one. A fortnight later, Ronaldo scores twice from the penalty spot: Inter two, Fiorentina nil. As Lazio and Milan continue to win, the slide continues: a draw with Bari, a thrashing at Bologna, defeats to Juve and second-bottom Sampdoria.

There is something of the Greek tragedy about Fiorentina, able to see the oncoming catastrophe, but unable to avert fate and its horrors as their scudetto challenge drifted away. Like the nightmares of a child who tries to run from a pack of dogs, but finds his feet somehow glued to the floor, Fiorentina are chased down by their bigger-name rivals. The shock and awe of those autumn afternoons, spattered with the humiliation of machine-gunned defenders and the image of a rampant Batistuta tearing away from goal in celebration – twice, three times per game – is a distant memory. Milan take the title, Lazio are second. Fiorentina aren’t even in the frame. A violent romance becomes the tragedy of La Viola.

There is, too, something of a

fin-de-siècle in Fiorentina’s sudden rise and fall. Serie A is starting to lose its lustre at the turn of the century, as talent seeped away into the Spanish and English leagues. But in Fiorentina – hardly built on mountains of lire – there is a final, heroic, futile flourish. British viewers had been fed on a rich diet of Channel Four’s Football Italia throughout the 90s, stretching back to Gascoigne’s years at Lazio. Interest is slightly muted by ’98; La Viola are the sweet after-dinner spirit: bang! bang! bang! to the shots from Batistuta’s right boot.

Fiorentina required a final-round draw against Cagliari to salvage third place and a slot in the Champions League – where, in some kind of semi-cathartic footnote, Batistuta scored in victories against Arsenal and Manchester United. But the longer story is sadder, as years of financial mismanagement under the regime of Cecchi Gori told and the side fell apart. In 2002, a weak Fiorentina bearing little resemblance to the side of ’98-’99 were relegated from Serie A, went into administration, and entered a free-fall which saw them denied entry to Serie B and forced to play in the regional Serie C2. Batistuta, meanwhile, finally won the league title – with Roma, where he had moved for the rather

ancien régime sum of 70 billion lire in 2000. But the title he craved so much, one gained at his beloved La Viola, once within his grasp, had slid away, leaving only flickering ciné-reels of memory, blurred by the raindrops of that fateful February afternoon.

What formation do you think Italy played in 1982?

I just realised why TRV systematically avoids sharemytactics

I just realised why TRV systematically avoids sharemytactics