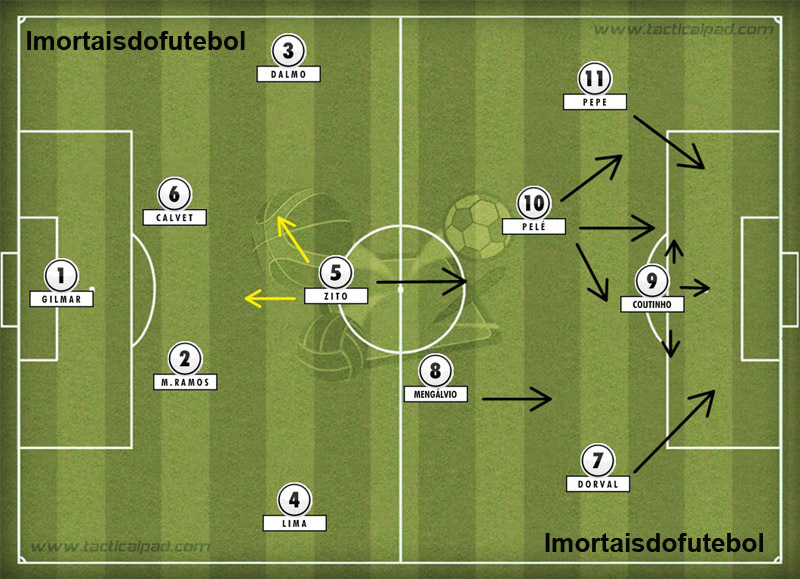

Pelé was a true number 10: his position on field and the formations from the golden age of Brazilian football

Posted by Otávio Pinto on 14 de julho de 2016

In order to understand Pelé’s position on field, it is necessary to explain the tactical formation of Brazilian football during his reign. Almost every Brazilian team played in a 4-2-4, organized like this (adapted, not literal translation):

goleiro (goalkeeper); lateral direito (right-back),

quarto-zagueiro (centre-back on the left),

zagueiro central (centre-back on the right) and

lateral esquerdo (left-back);

médio-volante (defensive midfielder) and

meia-armador (midfield playmaker; also called

meia-direita);

ponta-direita (right winger),

centroavante (centre forward),

ponta de lança (literally “spearhead”, to be explained later) and

ponta-esquerda (left winger) — about the origin of such terms, I recommend reading

an article in Portuguese written by experienced Brazilian journalist Alberto Helena Júnior).

The most traditional number assignment from midfield to attack was this: 5,

volante; 8,

meia-armador; 7,

ponta-direita; 9,

centroavante; 10,

ponta de lança; and 11,

ponta-esquerda. About the number 10, it is important to inform that it only became a synonym of the

ponta de lança after Pelé wore it in 1958 (Brazil’s numbers were determined randomly).

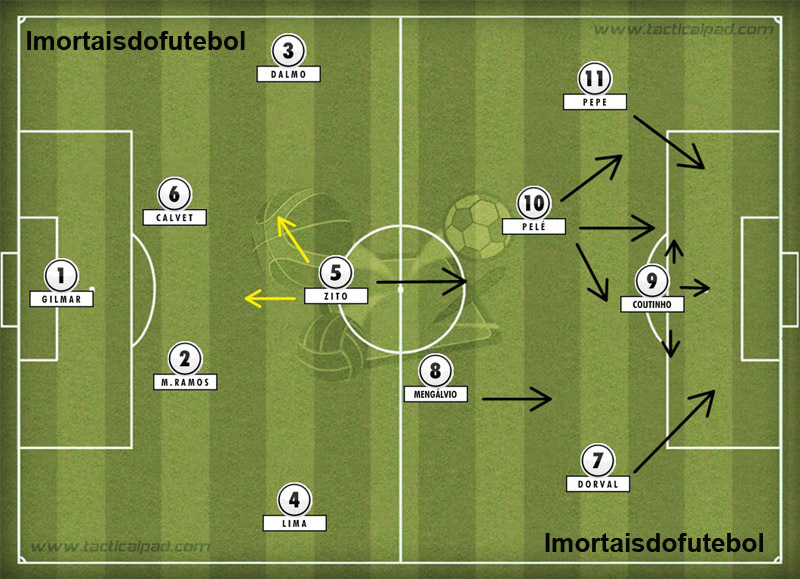

Botafogo, Brazilian Champions in 1968, and the Santos, that won basically everything in 1962, strictly followed that criteria (none the less, some times, like Cruzeiro, used to invert numbers 8 and 10: Tostão,

ponta de lança, played with the 8, Dirceu Lopes,

meia-armador, wore the 10):

In this classical formation, the team’s main organizer was the

meia-armador (responsible mainly for playmaking; usually did not score much). However, the

ponta de lança (regularly the team’s leading scorer), besides going forward to make plays with the

centroavante, had a double job, because he also went back to help the meia-armador in making plays; that was the famous “8 and 10” duo in the midfield.

To illustrate what was explained above, Santos formation in 1962 (very nice work done by the excellent webpage “

Imortais do futebol“; personally, I would add an yellow arrow going back for Pelé, showing his retreating to midfield during parts of the game):

One can notice that, during a significant part of the game, the

ponta de lança played behind three other forwards (

pontas and

centroavante), specially when coming back to make plays. When he went on to the attack, he would make a duo with the most advanced player, o

centroavante.

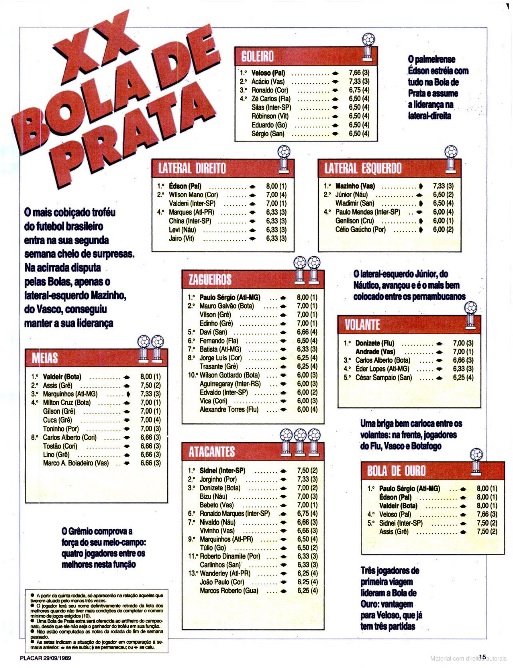

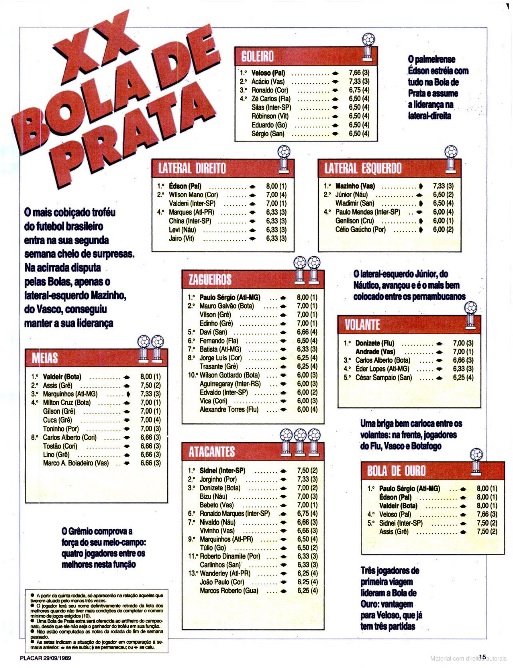

Few Brazilians know that this division of roles remained predominantly in Brazilian football until the end of the 80’s. In 1988 it was still used for the “Bola de Prata”, awarded by “Revista Placar” (the most famous football magazine in the country) to best players (by position) of the national league (notice that the great Zico is in the list as a

ponta de lança; pay attention, those are only the preliminary results from that year):

Revista Placar, n. 962, 11/11/1988.

Only in 1989, (picture below), the magazine went on to make a team with: two “Meias” (attacking midfielders), putting both

meia armador and

ponta de lança into the same position (for example, Cuca and Toninho,

pontas de lança in 88, were placed as “Meias” in 89); and three

atacantes (forwards), placing both wingers and centre-forwards in the same spot. From 1996 on, another defender was added in place of a forward in the final team of the year — both remaining forwards were usually a duo of a second striker and centre-forward).

Revista Placar, n. 1007, 09/29/1989.

1958 and 1970 Brazil

That foundation was kept throughout the 60’s, 70’s and 80’s, but, we still saw changes, innovations and adaptations in the period, mostly in the Brazilian National Team in World Cups.

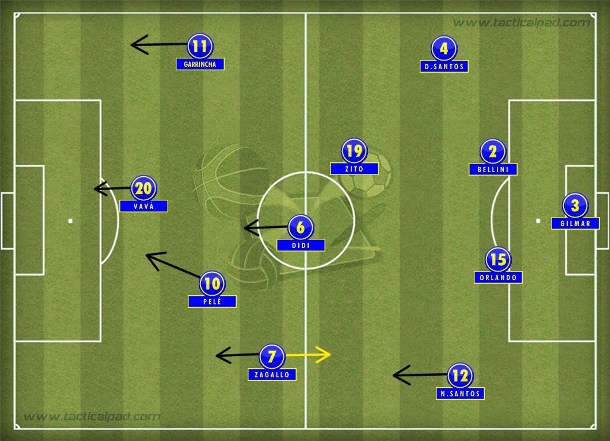

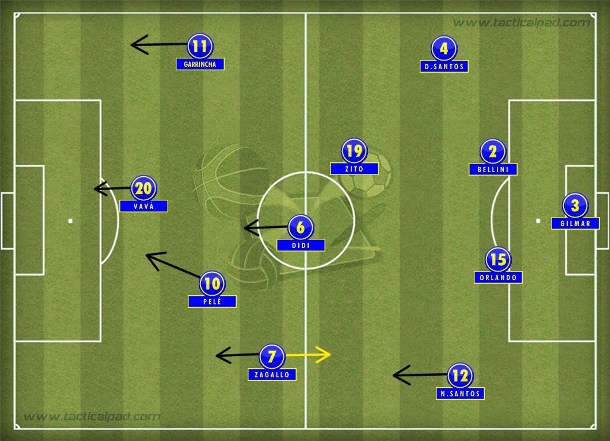

In 1958, Zagallo,

ponta esquerda (left winger), was brought to the midfield, and Brazil played in a 4-3-3.

1958 Brazil by André Rocha.

1958 Brazil by André Rocha.

Brazil in the 1970 World Cup, as explained by the competent Brazilian journalist, André Rocha (free translation here and everywhere else):

The magical national team of the “number 10’s”, chosen as the best of all time did not dominate solely on talent. Prior to that, there was a good execution of the 4-3-3 that, seen today, was a perfect 4-2-3-1 with only Tostão upfront, without the ball and with great mobility. Also speed in counter attacks, deciding most games in the second half because of the team’s great psychical training .

1970 Brazil by André Rocha.

1970 Brazil by André Rocha.

Zagallo, Brazil’s coach in that World Cup, stated another characteristic of that unforgettable team: “

We defended in a 4-5-1. Only Tostão stayed upfront. But even he went back, if needed“.

It is usually claimed that the Seleção in 1970 played with five “number 10’s”. In their teams, Rivellino, Gérson (at São Paulo FC in that year), Jairzinho and Pele, played with that number. However, in regards to what really meant to be a “10”, Brazil had four of such players (since Gérson was a

meia armador): Rivellino (who also could play as a

meia-armador, but he won his only “Bola de Prata” as a

ponta de lança), Tostão (although he wore the 8 for Cruzeiro), Pelé and Jairzinho (

“I was a ‘ponta de lança’ a number 10”; Rogério was the right-winger for Botafogo).

PELE’S POSITION

Some journalists and football fans, when discussing a “true number 10”, usually mention Maradona, Zidane, Zico, Platini, among others. A few of them define Pele like that. However, from the information reported here and later on, I believe it’s possible to state that Pele was a “true number 10”, like Zico, Platini and Maradona. The more careful reader notices that I did not mention Zidane. Yes, in my opinion, Zizou, in the Brazilian tradition, was closer to the old number 8, the

meia armador. Let’s see, the main playmaker of his teams, the French player did not use to enter much the opponent area and scored very few goals (0.19 career average). On the other hand, players in the mold of Zico, Pelé, Platini and Maradona, helped in making plays, but were also great scorers with goal averages considerably superior to Zidane’s in official games: Platini and Maradona with a little more than 0.5 per game; Zico, approximately 0.7; and Pelé, 0.93. Because of that, I consider a mistake to talk about a “true number 10”, as someone supposed to be “the brain of the team” (the main playmaker), because that was the role of “the true number 8”.

1981 Flamengo by André Rocha

1981 Flamengo by André Rocha. Notice how the traditional tactical base (with small variations) is still there: :

volante (Andrade),

meia-armador (Adílio),

ponta de lança (Zico),

ponta-direita (Tita),

centroavante (Nunes) and

ponta-esquerda (Lico).

.

.