India Is No Longer India

Exile in the time of Modi

Aatish Taseer May 2020 Issue

“You realize,” a friend wrote to me from Kolkata earlier this year, “that, without the exalted secular ‘idea’ of India … the whole place falls apart.”

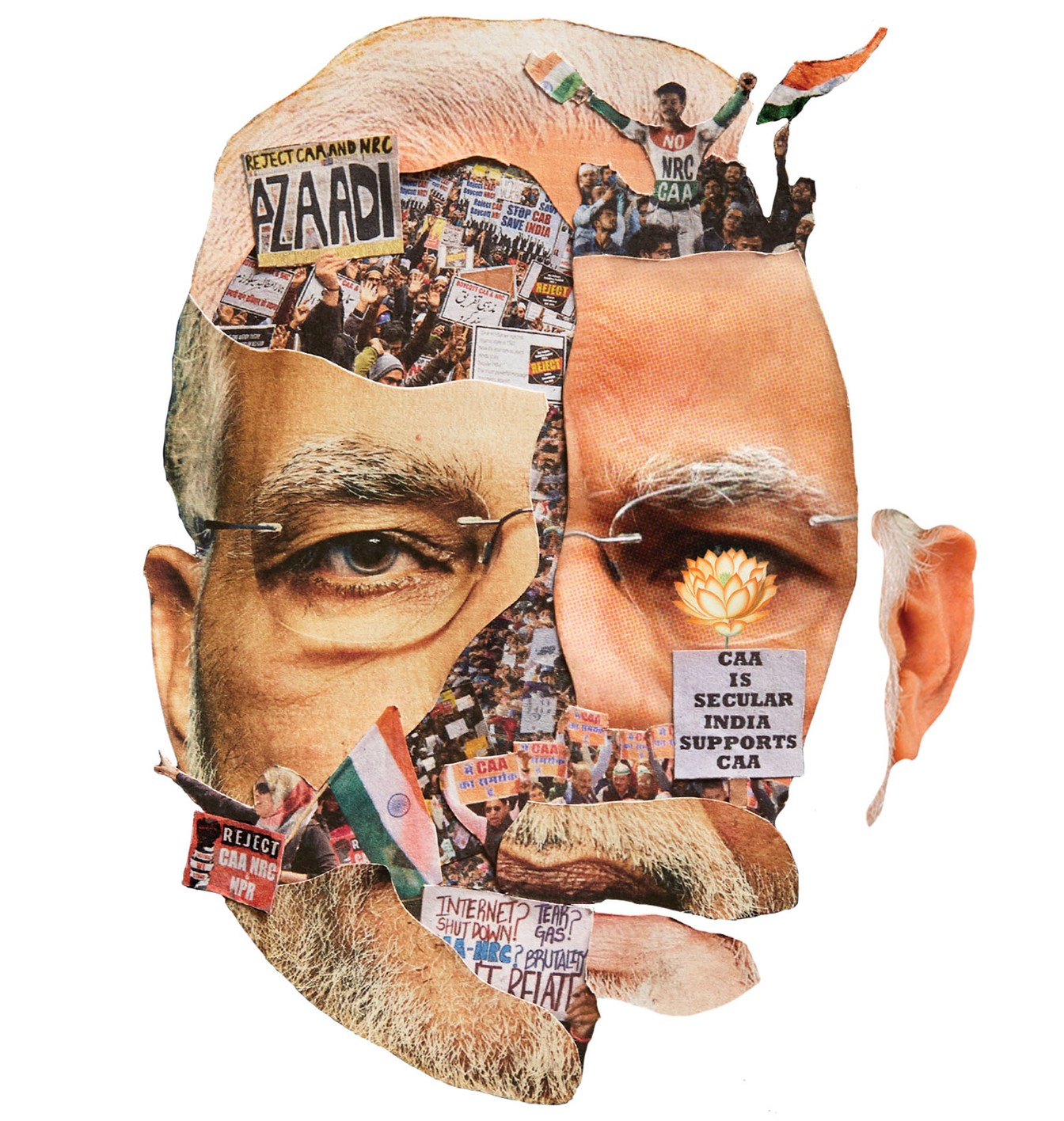

India had been on the boil for weeks. On December 11, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu-nationalist government had passed its Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which gave immigrants from three neighboring countries (Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh) a path to citizenship on one condition: that they were not Muslim. For the first time in India’s long history of secularism, a religious test had been enacted. If some commentators described the CAA as “India’s first Nuremberg Law,” it was because the law did not stand alone. It worked in tandem, Indian Home Minister Amit Shah menacingly implied—in remarks he has recently tried to walk back—with a slew of other new laws that cast the citizenship of many of India’s own people into doubt. Shah, who has referred to Muslim immigrants as “termites,” spoke of a process by which the government would survey India’s large agrarian population, a significant portion of which is undocumented, and designate the status of millions as “doubtful.” The CAA would then kick into action, providing non-Muslims with relief and leaving Indian Muslims in a position where they could face disenfranchisement, statelessness, or internment. India’s Muslim population of almost 200 million, which had been provoked by Modi’s government for six years, finally erupted in protest. They were joined by many non-Muslims, who were appalled by so brazen an attack on the Indian ethos. The constitutional expert Madhav Khosla recently described the effect of the new laws as a swift movement toward “an arrangement where citizenship is centered on the idea of blood and soil, rather than on the idea of birth.” In short, an arrangement in which being Indian meant accepting Hindu dominance and actively eschewing Indian Muslims.

India was seething, but I could not go back to the country where I had grown up. I was deep in my own citizenship drama. On November 7, the Indian government had stripped me of my Overseas Citizenship of India and blacklisted me from the country where my mother and grandmother live. The pretext the government used was that I had concealed the Pakistani origins of my father, from whom I had been estranged for most of my life, and whom I had not met until the age of 21. It was an odd accusation. I had written a book,

Stranger to History, and published many articles about my absent father. The story of our relationship was well known because my father, Salmaan Taseer, had been the governor of Punjab, in Pakistan, and had been assassinated by his bodyguard in 2011 for daring to defend a Christian woman accused of blasphemy.

None of this had affected my status in India, where I had lived for 30 of my 40 years. I became “Pakistani” in the eyes of Modi’s government—and, more important, “Muslim,” because religious identity in India is mostly patrilineal and more a matter of blood than faith—only after I wrote a story for

Time titled “India’s Divider in Chief.” The article enraged the prime minister. “

Time magazine is foreign,” he responded. “The writer has also said he comes from a Pakistani political family. That is enough for his credibility.” From that moment on, my days as an Indian citizen were numbered.

In August, I received a letter from the Home Ministry threatening me with the cancellation of my citizenship status. Then, in November, an Indian news site leaked what the government was planning to do. Within hours, the Home Ministry’s spokesperson was on Twitter, canceling my citizenship before I had been officially informed.

In one stroke, Modi’s government cut me off from the country I had written and thought about my whole life, and where all the people I had grown up with still lived.

To lose one’s country is to know a feeling akin to shame, almost as if one has been disowned by a parent, or turned out of one’s home. Your country is so intimately bound up with your sense of self that you do not realize what a ballast it has been until it is gone. The relationship is fundamental. It is one of the few things we are allowed to take for granted, and it is the basis of our curiosity about other places. Without a country we are adrift, like people whose inability to love another is linked to an inability to love themselves.

For me, the loss was literal—I could not go back to India—but also abstract: the loss of an idea, that “exalted” idea of a secular India. India, as its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, vowed, was not meant to be a “Hindu Pakistan.” Rather, it was to be a place that cherished the array of religions, languages, ethnicities, and cultures that had taken root over 50 centuries.

Nehru’s idea of India as a palimpsest, where “layer upon layer of thought and reverie had been inscribed, and yet no succeeding layer has completely hidden or erased what has been written previously,” served as the foundation for the modern republic, born of British colonial rule in 1947. The new country gave secularism a distinctly Indian meaning.

As the parliamentarian Shashi Tharoor told me recently, “Secular in India merely meant the existence of a profusion of religions, all of which were allowed and encouraged by the state to flourish.” The idea of India was a historical recognition that over time—and not always peacefully—a great diversity had collected on the Indian subcontinent. The modern republic, as a reflection of that history, would belong not to any one group, but to all groups in equal measure.

But beneath the topsoil of this modern country, a mere seven decades old, lies an older reality, embodied in the word Bharat, which can evoke the idea of India as the holy land, specifically of the Hindus. India and Bharat—these two words for the same place represent a central tension within the nation, the most dangerous and urgent one of our time. Bharat is Sanskrit, and the name by which India knows herself in her own languages, free of the gaze of outsiders.

India is Latin, and its etymology alone—the Sanskrit

sindhu for “river,” turning into

hind in Persian, and then into

indos in Greek, meaning the Indus—reveals a long history of being under Western eyes. India is a land; Bharat is a people—the Hindus. India is historical; Bharat is mythical. India is an overarching and inclusionary idea; Bharat is atavistic, emotional, exclusionary.

It was this tension between two distinct ways of looking at the same place—modern country or holy land—that the founder of Hindu nationalism, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, took aim at in the early 20th century. As he wrote in his 1923 book,

Hindutva: Who Is a Hindu?, “To be a Hindu means a person who sees this land, from the Indus River to the sea, as his country but also as his Holy Land.” This Hindu person was, in Savarkar’s view, the paramount Indian citizen. Everyone else was at best a guest, and at worst the bastard child of foreign invasion. Savarkar was, as Octavio Paz writes in

In Light of India, “intellectually responsible for the assassination of Gandhi,” in 1948, at the hands of Nathuram Godse, now a hero of the Hindu right. Modern Hindu nationalism is represented by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the cultural organization in which Narendra Modi was reared, and of which his party—the Bharatiya Janata Party—is the political face.

As much as people in India bridle against the binary distinction of India and Bharat, it recurs again and again in the country’s discourse—Bharat as a pure, timeless country, unassailable and authentic; India as the embodiment of modernity and all its ills and dislocations. When a medical student was raped and murdered in Delhi in 2012, the head of the RSS had this to say: “Such crimes hardly take place in Bharat, but they occur frequently in India … Where ‘Bharat’ becomes ‘India,’ with the influence of Western culture, these types of incidents happen.”

Growing up in 1980s India, in a Westernized enclave where, to quote Edward Said, the “main tenet” of my world “was that everything of consequence either had happened or would happen in the West,” I had no idea of this other wholeness called Bharat.

That ignorance of Hindu ways and beliefs was not mine alone, but symptomatic of the English-speaking elite, which, in imitation of the British colonial classes, lived in isolation from the country around them. Mohandas Gandhi, at the 1916 opening of Banaras Hindu University, a project that was designed to bridge the distance between Hindu tradition and Western-style modernity, worried that India’s “educated men” were becoming “foreigners in their own land,” unable to speak to the “heart of the nation.” Working closely with Nehru, Gandhi had been a great explainer, continually translating what came from outside into Indian idiom and tradition.

By the time I was an adult, the urban elites and the “heart of the nation” had lost the means to communicate. The elites lived in a state of gated comfort, oblivious to the hard realities of Indian life—poverty and unemployment, of course, but also urban ruin and environmental degradation. The schools their children went to set them at a great remove from India, on the levels of language, religion, and culture. Every feature of their life was designed, to quote Robert Byron on the English in India, to blunt their “natural interest in the country and sympathy with its people.” Their life was, culturally speaking, an adjunct to Western Europe and America; their values were a hybrid, in which India was served nominally while the West was reduced to a source of permissiveness and materialism.

They thought they lived in a world where the “idea of India” reigned supreme—but all the while, the constituency for this idea was being steadily eroded. It was Bharat that was ascendant. India’s leaders today speak with contempt of the principles on which this young nation was founded. They look back instead to the timeless glories of the Hindu past. They scorn the “Khan Market gang”—a reference to a fashionable market near where I grew up that has become a metonym for the Indian elite. Hindu nationalists trace a direct line between the foreign occupiers who destroyed the Hindu past—first Muslims, then the British—and India’s Westernized elite (and India’s Muslims), whom they see as heirs to foreign occupation, still enjoying the privileges of plunder.

Almost 30 years ago, in the preface to his book

Imaginary Homelands, Salman Rushdie, fearful of the “religious militancy” threatening “the foundations of the secular state,” had expressed alarm that “there is no commonly used Hindustani word for ‘secularism’; the importance of the secular ideal in India has simply been assumed, in a rather unexamined way.” As it happens, the exalted idea of India has no commonly used translation either. Rushdie was saying that this is not merely a failure of language, but an expression of the isolation of an elite that thought its power was inviolable. “And yet,” Rushdie wrote, “if the secularist principle were abandoned, India could simply explode.”

India is now exploding. Even the visit of an American president in February was not enough to contain the rage. As Modi and Donald Trump bear-hugged each other, Hindu-nationalist mobs roamed the streets of New Delhi a few miles away, murdering Muslims and attacking their businesses and places of worship. The two leaders did not acknowledge these events, in which Hindus and Muslims alike were killed. India is approaching an especially dangerous point: the right quantity of unemployed young men, the right kind of populist strongman, and the right level of ignorance and heightened expectations, emanating from an imaginary past. Who knows what elements of modern nation-building and democracy might conveniently be sacrificed on the altar of a vengeful and revivalist politics?

I was not Muslim, and not Pakistani, but, as the writer Saadat Hasan Manto once noted, I was Muslim enough to risk getting killed. It was game over for my sort of person in India. We had been so blithe, so unknowing, so insulated from a wider Indian reality that it was as if we had prepared the conditions for our own destruction.

If I became attuned to the danger, it was because I had seen what had happened to my father in Pakistan, where the shape of society is identical to that of India. He had died like a dog in the street for his high Western ideals. They mourned him in the drawing rooms of Lahore, and in the universities, think tanks, and newsrooms of the West. But in Pakistan, his killer was showered with rose petals; his killer’s funeral drew more than 100,000 mourners into the streets.

All over the old non-West, as well as in Western Europe and America, the symbols of belonging—race, religion, language—are being repurposed for a confrontation between what David Goodhart has referred to as the “somewheres” and the “anywheres,” the rooted and the rootless. I, with no tribe or caste, no religion or country, have had nowhere to go but to the cities of the West, where I hoped to wait out the storm. But, as my break with India acquired a cold new finality, exile turning into asylum, I could not help but ask whether any harbor would survive the destructive wrath of what may be coming for us all.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/05/exile-in-the-age-of-modi/609073/