antohan

gets aroused by tagline boobs

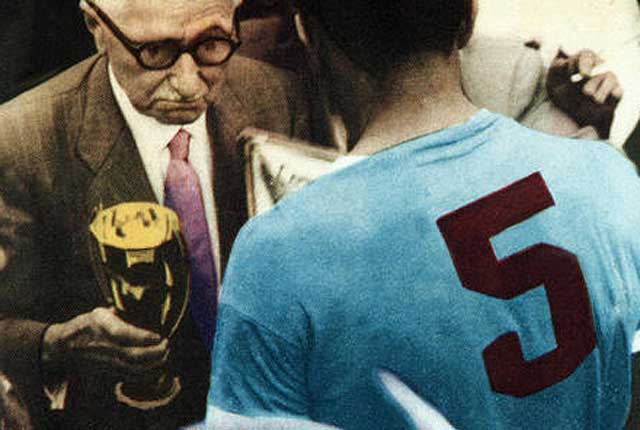

Obdulio Jacinto Varela – “El Negro Jefe” (Peñarol, 1953-54)

The man who silenced the Maracanã before Schiaffino made it tremble and Ghiggia reduced it to tears. You’ve heard it all before: beastly midfielder, dominant, capable of executing the most influential and game-defining World Cup Final individual performance. He could sit and protect the defence, passing the ball short and long to good effect, or operate as a box-to-box midfielder with a thunderous long range cannon of a right peg.

You’ve also read my ranting about him being at his b est surrounded by his own, players with shared histories, identities, philosophies, idiosyncracies… There was a massive dimension to him as a player and captain which requires this, place him in a ragged band of superstars and his impact would be hugely diminished. I stand by that (and you’ll probably “get it” from the rest of this post), which is why I want him at the heart of this “Gianni Brera mind blown best of Italy and Uruguay” composite.

What you probably haven’t read about is how he raised that late 40s side as captain, and how he saw it out, saw the Death Squad disband, and the key players he groomed leave… and stooped and started again with worn out tools. No, he didn’t play much beyond them, but he carried on until he knew it was all on track with William Martínez arriving to captain the side for the next seven years. Once his legs went, he stayed on as coach/advisor/whatever it was until the giant hole he had left in midfield had been filled satisfactorily by someone equally capable of demanding order and total commitment in the midfield, the backline behind it, and the forwards ahead.

Peñarol’s training ground “Las Acacias” was his home for over a decade. In particular, there was one tree where he held court with each and every player, always individually, and paying particular attention to the youth prospects. He imposed respect -not fear- among his teammates, although everyone hoped he would arrive whistling a tune as an indication he was in a good mood that day. He imparted wisdom, never raised his voice or needed to speak out of turn. He kept quiet most of the time, listening, observing, and when he made the slightest motion indicating he was about to speak everyone would shut up and stay expectant to what would be no doubt a lesson worth learning. He had the power of synthesis (I sure don’t!), the ability to dissect a game and occasion and home in on what was wrong, what was the root cause, with laser precision. And then he acted and directed on his insights, expertly.

The arrival of Ghiggia and Hohberg was the inception of the Death Squad. In 1949, they averaged four goals a game while conceding one: 5-0, 5-2, 3-0, 3-1, 6-1, 6-0 and 5-3 was their form sheet prior to the derby against Nacional. The day before it, he dedicated an entire hour to each of them individually, to make sure he got into their heads what it meant to play a derby, what it meant to wear those colours on such a stage.

Hohberg tells us more about his one-to-one:

OJV: I know you boys have been pummeling the smaller teams, people are excited… but this is different.

JEH: I know, it’s a big game.

OJV: Yes, but also big players. You know who is marking you tomorrow?

JEH: “El Cato” Tejera [1950 WC winner]

OJV: And you know what he will do, right?

JEH: He will kick me all game.

OJV: No, he won’t. He will test you. He will try to get under your skin, in your head, losing focus, and if he succeeds he won’t need to kick you all that much. You will have a poor game anyway, and if you have a poor game it will be hard for Ghiggia not to [since they were inside right and outside right respectively]. That’s half the battle won for them.

JEH: I understand, don’t worry.

OJV: This is what will happen. In the first five minutes of the game, as soon as he gets an opportunity he will play a dirty trick on you. You will take it, you won’t complain, you won’t shout anything at him or cry like a baby to the ref, or point fingers at him. You’ll just stand up and keep going.

JEH: Yes, Sir.

OJV: The next time I get the ball, I’ll play it in between you two. 50-50. And you know what you will do?

JEH: Yes, I know

For the record, it didn’t mean breaking his leg or anything, it meant going for that ball with complete abandon and showing no amount of dirty tricks were going to subdue him. That he could give as good as he got and the occasion didn’t get to him.

The next day, there’s a corner two minutes into the game and Hohberg suddenly feels a searing pain which makes him arch forth and fall on his side gasping for air. Tejera had elbowed him. No complaints.

A few minutes later Obdulio gets the ball, looks ahead, sees Hohberg alert and moving to make the space for him to pass into, nods his head knowingly and places it bang in the middle. Crunching tackle, and Tejera had got his message: he couldn’t make the connection break down, which was probably the easy win game-plan he had dwelled on all week. Soon after Ghiggia scored, and five minutes before half time Tejera brought down Hohberg in the box: penalty. Tejera loses the plot screaming bloody murder at the ref and gets sent off. The penalty is taken by Míguez, saved, but Vidal scores from the rebound. Nacional players are by now all over the place. They know they are completely dominated and destined to lose by a basketball score. They surround the ref, the centre-forward kicks him and is also sent off…

Nacional never came back for the second half. There have been big scorelines through history, but the shame of running away from the stadium to avoid humiliation will forever hang on their heads. And it all started and the game was won in the course of a one hour chat under an acacia tree.