Wasn't sure where else to put this, prob not worth its own thread.

http://uk.askmen.com/sports/fanatic/why-man-u.html

Visiting Manchester the other day, I was driving down a nondescript road past dreary shops and offices when I saw the top of a sports stadium poking into the gray sky. It was Old Trafford. Team buses carrying soccer players from more glamorous cities such as Barcelona have been known to echo with cries of disgust as they pull in here.

The home of Manchester United is rainy and underwhelming. The estimated 333 million humans who consider themselves United fans don’t all know that Manchester is a city in England, but many of those who do would probably be surprised to find just how mid-ranking a city it is. Yet when United’s American ruling family, the Glazers, sold club shares in August, United was valued at $2.3 billion. That made it the world’s most valuable sports franchise, ahead of Real Madrid and baseball’s New York Yankees, according to Forbes. In short, United is bigger than Manchester. So why on earth did this global behemoth arise precisely here? And how, in the last 134 years, has United shaped soccer, in England and now the world?

When a soccer club was created just by the newish railway line in 1878, the Manchester location actually helped. The city was then growing like no other on earth. In 1800 it had been a tranquil little place of 84,000 inhabitants, so insignificant that as late as 1832 it didn’t have a member of parliament. The Industrial Revolution changed everything. Workers poured in from English villages, from Ireland, from feeble economies everywhere (my own great-grandparents arrived on the boat from Lithuania). By 1900, Manchester was Europe’s sixth-biggest city, with 1.25 million inhabitants.

The club by the railway line was initially called Newton Heath, because the players worked at the Newton Heath carriage works of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company. They played in work clogs against other work teams. Jim White’s Manchester United: The Biography nicely describes the L&YR workers as “sucked in from all over the country to service the growing need for locomotives and carriages.” Life in Manchester then was neither fun nor healthy, White writes. In some neighborhoods, average male life expectancy was just 17. This was still the same brutal city where a few decades before, Karl Marx’s pal Friedrich Engels had run his father’s factory. The conditions of the industrial city were so awful it inspired communism. (My own great-grandparents lost two of their children to scarlet fever in Manchester before moving on to much healthier southern Africa.)

Inevitably, most of these desperate early Mancunians were rootless migrants. Unmoored in their new home, many embraced the local soccer clubs. Gathering together at Old Trafford must have given these people something of the sense of community that they had previously known in their villages. That’s how the world’s first great industrial city engendered the world’s greatest soccer brand.

United grew into a big English club, but for long it wasn’t particularly brilliant. From 1878 through 1955 it won just three English titles. United became different from other clubs on February 6, 1958, the day a twin-engine British European Airline plane crashed on its third attempt to take off from an icy Munich airport. On board was Manchester United’s team.

The “Busby Babes,” named for their Scottish manager Matt Busby, had been a gifted young side playing glorious attacking soccer. Eight of the players --including the great 21-year-old Duncan Edwards --were among the 23 people killed in the crash. A tearful nation followed Busby’s own struggle for life in a Munich hospital. White writes that for those who now try to make money out of United, Munich is the “ marketing core from which everything else has stemmed.” It became the first pillar of United’s global brand.

Busby recovered, and with players bought from other clubs, United reached the FA Cup final that same May. He built a new team around Bobby Charlton (who, aged 20, had also been on the plane), Denis Law and George Best. Playing glorious attacking soccer, it crushed Benfica 4-1 in the European Cup final of 1968. Tragedy and rebirth had given United a story.

The club then languished for 25 years, with only its violent “Red Army” of fans to add to its glamour. When Alex Ferguson became manager in 1986, he spoke to everyone at Old Trafford -- from former legends to window-cleaners -- and was astounded at the gap between the team's giant self-image and puny results. Still, Ferguson absorbed three tenets of United’s brand: United teams must attack, the world is against United and United is more a cause than a soccer club. He also made himself part of United’s brand. When he said “I am like the keeper of the temple,” he meant that the cause had become almost unthinkable without

By the early 1990s, as Ferguson’s United started to win titles, a marketing genius named Edward Freedman was turning the club’s brand into gold. Hardly anyone has heard of Freedman, but he was almost as central to the club’s rise as Ferguson himself.

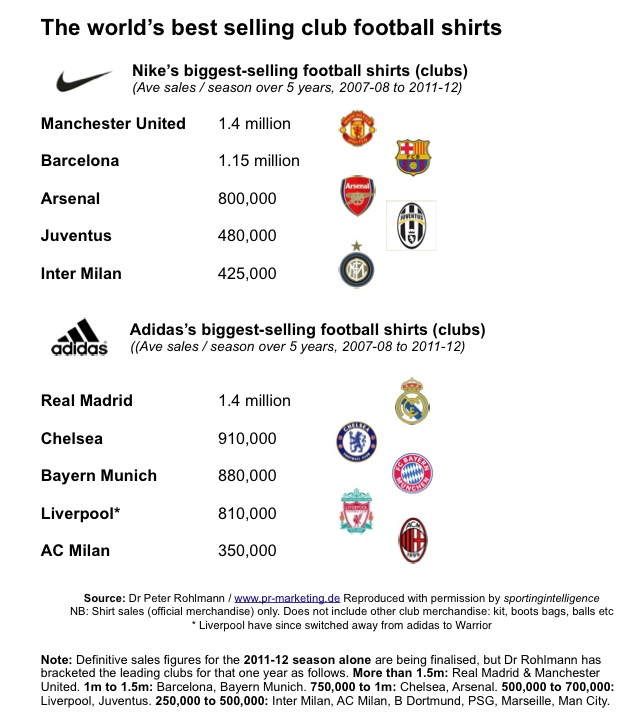

A Londoner who oversaw merchandise at Tottenham in the 1980s, Freedman had yearned to join United because he realized the immensity of the club’s brand. It appalled him, he told me, that United made so little money from it. When he arrived at Old Trafford in 1991, fans could buy little more than a United scarf and shirt. Pirates did sell T-shirts yards outside the grounds, but not a penny of their takings went to the club. Freedman argued that United had a bigger global brand than Nike. After all, Nike was paying United money to put its name on United’s shirts, instead of United paying Nike.

Soon a megastore opened at Old Trafford. Shops around Britain and later abroad began carrying United paraphernalia. Freedman helped develop a range of over 1,000 United products. In 1992 United had had a commercial income of £1.2 million. By 1997, when Freedman left, its merchandising revenues were £28 million. It wasn’t simply that Freedman had exploited United’s brand; by exploiting it, he helped grow it. Meanwhile, almost all other clubs, either secretly or openly, envied United’s commercial success and tried to copy it. United has marked soccer's history more through its brilliant originality off the pitch than on it. (Its three European titles are credible but don’t even match Ajax or Liverpool.)

In the 1990s, the new money, Ferguson’s cunning and a chance generation of great youngsters like David Beckham, Paul Scholes, Ryan Giggs and the Neville brothers finally brought United success. From 1993 to 2003, the club won eight league titles -- more than in all its previous history -- and the Champions League in an unforgettable final in 1999. Moreover, Beckham and Eric Cantona became individual icons arguably as big as the club itself. Like Best, these men were pop stars dressed up as soccer players. Arsenal and Liverpool have had many great players, but never pop stars of this order. Much as Beckham’s fame irritated Ferguson -- in 2003, the manager kicked a boot in his face -- the world’s best-known athlete helped United become the world’s best-known sports club. Happily for United, this happened simultaneously with the so-called third wave of globalization. From the 1990s, cable TV and internet created new United fans around the world.

United became beloved, but it also became hated. Even at England internationals you could sometimes hear the familiar chant, “Stand up if you hate Man Utd.” Partly it was because the team won so often. But partly, too, United’s knack for making money was widely considered somehow unsporting (especially the year it unveiled a “third kit” that existed solely to sell replica shirts to gormless children).

United acquired the nickname Merchandise United. The club’s brand -- buffered by Munich, pop stars and prizes -- gained a new, unwanted core value in the 1990s: It came to be seen as representing corporate greed. That only worsened after the Glazers acquired the club between 2003 and 2005 with the sole aim of taking money out of it. It didn’t help that United’s players, the brand’s main carriers, kept getting richer. In the 1990s, Teddy Sheringham annoyed people by driving his Ferrari down Manchester’s Deansgate. By 2010, it was Wayne Rooney threatening to join Manchester City unless United paid him £250,000 a week.

This disquiet is felt even by many United fans. The Glazers’ strategy of hiking ticket prices has caused widespread upset. Andy Walsh, chief executive of FC United, the local club founded as the anti-commercial antidote to Man United, has lamented, “I still consider myself a Manchester United fan; I can’t afford to go to games anymore.”

United fans come in all shapes and sizes, from lifelong locals like Walsh to eight-year-old girls in Los Angeles. However, they have collectively come to be derided as glory-hunters with no connection to the club. “You’re not from Manchester!” is a favorite chant of opposition fans trying to taunt United’s supporters. There is something to this: So global is the Red Army now that only a tiny proportion of the world’s United fans have ever even seen Old Trafford. Yet that doesn't seem to diminish the fervor. I have witnessed members of United’s Johannesburg fan club putting their entire beings into the chant “And we hate Scousers [people from Liverpool], and we hate Scousers!” even though few of them could have met a “Scouser” in their lives.

Supporting Manchester United has become a way for people from Burma to Nigeria to feel part of something indisputably world class. You see it on Twitter: Somebody might identify himself as “Mohammed from Jakarta,” and the thing he chooses to tell the world about himself in his brief biography is not his nationality or religion or job or family status but “100% Man Utd.” United has pulled off the admirable trick of becoming both global and locally rooted at the same time.

Critics have long been predicting that the moment United starts losing, the glory hunters will get bored and the hype will collapse. This is false. More likely, the club is only going to get bigger. In the seven seasons since the Glazers bought the club, United has won four Premier League titles and finished second three times. It has also reached three Champions League finals, winning one. This may be the most successful seven-year period in the club’s history. Meanwhile, hordes of people in China, India, Indonesia and the U.S. have only just discovered United. In a sports pub in San Francisco last year, I met a female psychologist, wearing a United shirt, who on first encountering soccer in 2010 had thought, “Why did nobody ever tell me about this before?” She hadn’t stopped watching since.

It’s because of people like her that Chevrolet recently paid $559 million to sponsor United’s shirts for seven years -- more than twice the annual amount the club gets from its current sponsor Aon. United should soon also benefit from a bumped-up deal for foreign TV rights to Premier League games, as ever more foreigners switch on. Anyone grumbling about how little Newton Heath lost its soul by becoming a global behemoth ain’t seen nothing yet.