39. Johnny Haynes, Isco. 9 points

Johnny Haynes

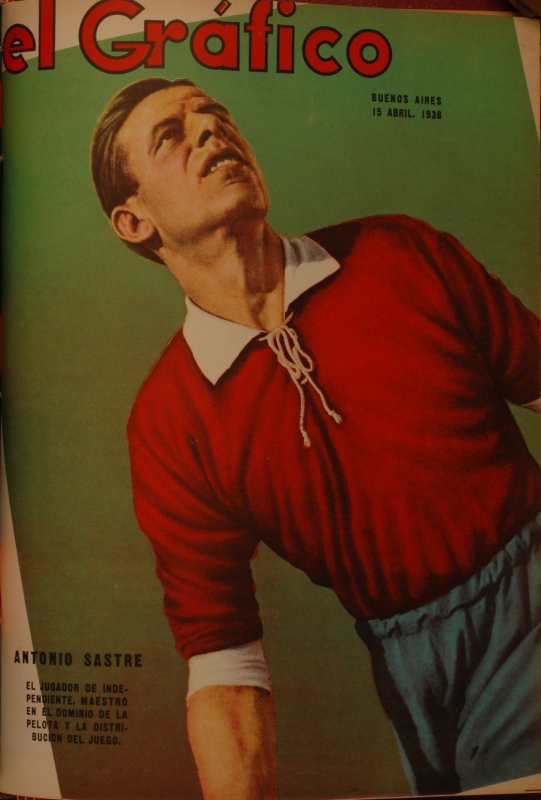

One of the most outstanding talents that England had in the 1950's-60's, Haynes was a magnificent playmaker with seemingly unlimited passing range. His signature move was the diagonal through-ball, often delivered blind and on the turn, as if Haynes could sense the opening without having to see it. Always a perfectionist, he demanded only the best from himself and from others. Pretty much all of his England partners, from Finney to Greaves, call him the greatest passer of the ball that they've seen (there's also a similar quote Pelé... the man loves his compliments). Allan Mullery's one was the most specific though: "Johnny was the greatest passer of a ball I’ve known. He could lay it within six inches of a colleague. A yard wasn’t good enough for Johnny." He was at the heart of England’s historic 9-3 defeat of Scotland in 1960. In the same year he was voted Sportsman of the Year — so when in 1961 he became the first £100-a-week footballer, nobody was surprised.

Sadly, his career for England was cut short by a horrible car accident. When a policeman found him, he cheerfully noted: "Don't worry son, you've only broken your legs" — but that phrase sounds very different when you're a professional footballer. After that injury, Haynes was never the same — and while he had managed to keep playing for Fulham for almost a decade, he never got another call up for England again (prior to the accident he had captained England 22 times, and, being only 27, was expected to lead them in the 1966 World Cup). Fulham, that reached 2 FA Cup semi-finals in 1958 and 1962 would struggle to remain competitive and Haynes would eventually retire with only 1 trophy to his name — a South African league title that he had won in a semi-retirement. With 658 games and 158 goals for the club, he is the greatest figure in Fulham's history rivalled only by Michael Jackson, who attended their game once.

Isco

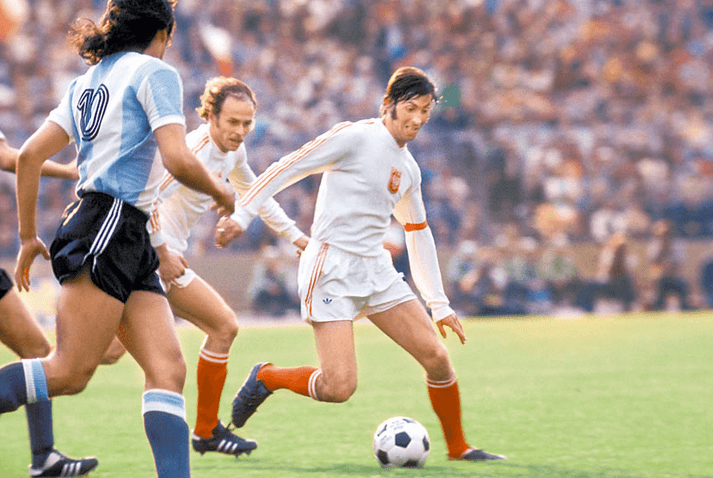

I'm a bit surprised by his inclusion and I don't think that I need to describe his (still on-going even though it doesn't feel like it) career in detail. When Isco & Thiago dominated the 2013 U-21 Euros it looked like the whole world is at their feet and the all-mighty Spain doesn't need to worry about its future with the replacements for Xavi & Iniesta already being ready. Isco, at the time Malaga player, had already shown his potential both in the league (securing their first victory over Real Madrid in 29 years) and in Europe — Malaga narrowly missed the semi-final with Reus & Santana (Dortmund would reach the final that year) scoring 2 decisive goals in the added time.

His dog named Messi ("I named my dog 'Messi' because Messi is the best in the world, and so is my dog" — you can't really argue with the logic) probably wasn't too happy with Isco's next move — he would sign for Real Madrid who were desperate to sign Spanish next big thing. He's been there for 8 years now, but he never really established himself as a key player of the starting XI — even though you can't dismiss his achievements there either. His trophy room with 4 CL & 2 La Liga titles is quite impressive, but a man of his talent should've played a bigger role in those — Isco usually played as a 12th man (first substitution for either creative midfielders or attackers) and didn't fully exploit Bale's horrible patch of form or Ronaldo's departure.

Johnny Haynes

One of the most outstanding talents that England had in the 1950's-60's, Haynes was a magnificent playmaker with seemingly unlimited passing range. His signature move was the diagonal through-ball, often delivered blind and on the turn, as if Haynes could sense the opening without having to see it. Always a perfectionist, he demanded only the best from himself and from others. Pretty much all of his England partners, from Finney to Greaves, call him the greatest passer of the ball that they've seen (there's also a similar quote Pelé... the man loves his compliments). Allan Mullery's one was the most specific though: "Johnny was the greatest passer of a ball I’ve known. He could lay it within six inches of a colleague. A yard wasn’t good enough for Johnny." He was at the heart of England’s historic 9-3 defeat of Scotland in 1960. In the same year he was voted Sportsman of the Year — so when in 1961 he became the first £100-a-week footballer, nobody was surprised.

Sadly, his career for England was cut short by a horrible car accident. When a policeman found him, he cheerfully noted: "Don't worry son, you've only broken your legs" — but that phrase sounds very different when you're a professional footballer. After that injury, Haynes was never the same — and while he had managed to keep playing for Fulham for almost a decade, he never got another call up for England again (prior to the accident he had captained England 22 times, and, being only 27, was expected to lead them in the 1966 World Cup). Fulham, that reached 2 FA Cup semi-finals in 1958 and 1962 would struggle to remain competitive and Haynes would eventually retire with only 1 trophy to his name — a South African league title that he had won in a semi-retirement. With 658 games and 158 goals for the club, he is the greatest figure in Fulham's history rivalled only by Michael Jackson, who attended their game once.

Isco

I'm a bit surprised by his inclusion and I don't think that I need to describe his (still on-going even though it doesn't feel like it) career in detail. When Isco & Thiago dominated the 2013 U-21 Euros it looked like the whole world is at their feet and the all-mighty Spain doesn't need to worry about its future with the replacements for Xavi & Iniesta already being ready. Isco, at the time Malaga player, had already shown his potential both in the league (securing their first victory over Real Madrid in 29 years) and in Europe — Malaga narrowly missed the semi-final with Reus & Santana (Dortmund would reach the final that year) scoring 2 decisive goals in the added time.

His dog named Messi ("I named my dog 'Messi' because Messi is the best in the world, and so is my dog" — you can't really argue with the logic) probably wasn't too happy with Isco's next move — he would sign for Real Madrid who were desperate to sign Spanish next big thing. He's been there for 8 years now, but he never really established himself as a key player of the starting XI — even though you can't dismiss his achievements there either. His trophy room with 4 CL & 2 La Liga titles is quite impressive, but a man of his talent should've played a bigger role in those — Isco usually played as a 12th man (first substitution for either creative midfielders or attackers) and didn't fully exploit Bale's horrible patch of form or Ronaldo's departure.

Last edited:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66719083/57003050.jpg.0.jpg)

:format(webp):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-7277327-1437849047-6457.jpeg.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66408820/279134.jpg.0.jpg)