Tuppet

New Member

Not you, you always cover your bases like the experienced drafter you are

everybody else is saying and voting on this assumption.

Not you, you always cover your bases like the experienced drafter you are

Actually I have no idea what is your defensive strategy here

I’ve voted to see score but know my vote doesn’t count. Hope that’s alright @Physiocrat

Figo is better than Becks in every sense apart from FK and long passes from deep. Figo is the better leader, better scorer, better dribbler, etc.I see many players in Tuppet's side where harms has no answer how to stop them. Di Stefano is too much for Lerby. Czibor is gonna beat his man time and time again and drill in those dangerous low crosses like he did for Puskas and like Gento did for Di Stefano. Also who is going to stop Beckenbauer? He can take teams apart alone with his runs and passing, yet there is no player assigned to contain him.

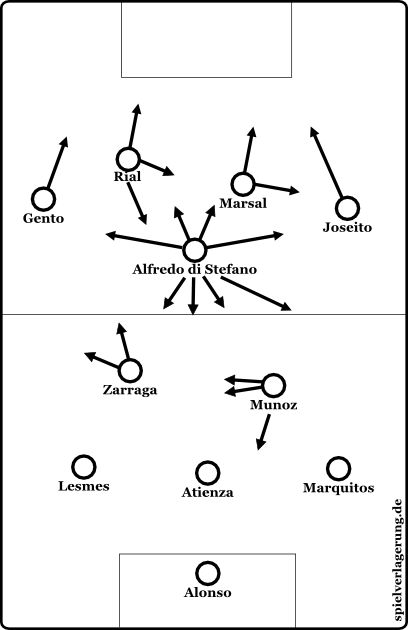

Feels like everything would look different when Tuppet had Maradona instead of Di Stefano here, despite the latter being the much better fit here. Simply because he has the work rate to defend against Suarez (or harms' midfield in general) while being just a bit worse attacking wise.

Harms' biggest advantage is actually on his left side, Rensenbrink AND Evra vs Benarrivo sounds deadly. Unless Bene is known as a hard working winger who tracks back constantly? Can't say anything about that. Otherwise I would bet on Rensenbrink to score for sure, maybe even twice.

I like the Suarez pick because he is a clear upgrade on Effenberg, who has never been a great defensive player either. I don't understand the Figo-Beckham change, you get more dribbling and pace (which your attack has in abundance) and lose work rate and defensive positioning which you badly needed and which the voters appreciated very much in your last games.

Di Stefano is probably the worst rated GOAT here(along with Cruyff). Often seen as a square peg in round hole in terms of fit and probably very few times seen as the star of the show in the same respect Maradona, Messi, Pele are..Aye, if anyone has been underrated in this game, it is Alfredo Di Stefano, of all players. Can't imagine him facing much resistance here whatsoever.

Figo is better than Becks in every sense apart from FK and long passes from deep. Figo is the better leader, better scorer, better dribbler, etc.

You might have a point in terms of putting Beckenbauer to the left as Bossis was a more conservative as a full back, but Benarrivo has always been excellent in both phases of the game and when he was needed to defend he could've play very conservative role either side without much hassle.I reckon Desailly is a Top tier CB (I'f put him in tier 1.5 per other thread).

Other point is having Beckenbauer and Benarrivo on same side. Both are attack minded players and without the calming impact of Schwarzenbeck in-between, I don't see it as perfect..

Not defensively which is what moby's team needed. His team was fine offensively, I would have upgraded the defense/midfield while keeping the attack the same.

Now they are better offensively but far worse defensively, his statement of transitioning to a 4-3-3 does not hold either.

Oh WTF !! I do deserve to lose for that.Alberto Di Stefano? I almost want to vote against @Tuppet just for that

Done.Oh WTF !! I do deserve to lose for that.

@Enigma_87 can you please update the formation pic I have sent you with correction.

Figo had a pretty good work rate. You do have a point but the gap between Figo's offensive contribution IMO would have a bigger impact in an isolated game than Becks defensive one.

In terms of the game in hand indeed in this set up harms team stylistically looks more as a 4-2-4 than 4-3-3 if Figo is playing in his favorite role.

You know that I have Bobby Moore, right? Vidić is covering Kocsis, Evra — Bene etc. Moore is a "free" defender who's going to pick Di Stefano when he comes close to the box — in addition to Lerby/Suarez who are going to help covering.I see many players in Tuppet's side where harms has no answer how to stop them. Di Stefano is too much for Lerby. Czibor is gonna beat his man time and time again and drill in those dangerous low crosses like he did for Puskas and like Gento did for Di Stefano.

Well, I said that Vidić is a stylistic match and one of the best possible fits for Kocsis, which I genuinely believe and I don't think that it's questionable. He won't stop him completely, but his strengths somewhat compensate those of KocsisNot you, you always cover your bases like the experienced drafter you are. Its a thing right, where we say "Not saying like x will completely stop y but " and then proceed to argue as if x has completely stopped y.

everybody else is saying and voting on this assumption.

You know that I have Bobby Moore, right? Vidić is covering Kocsis, Evra — Bene etc. Moore is a "free" defender who's going to pick Di Stefano when he comes close to the box — in addition to Lerby/Suarez who are going to help covering.

I mean Bossis-McNeill-Beckenbauer-Benarrivo + Desailly against Rensenbrink-Pelé-Law-Figo (let aside Suarez) is, supposedly, an answer?

@Joga Bonito

One of the reasons I keep mentioning in the GOAT context is because of this.

Okay, lets say I am underrating Lerby and Suarez both for some reason (I don't think I am but I'll play along as there will always be slightly different views. Its not like I am calling him Pirlo and you are calling him Desailly).

Do you think the pair is good enough to handle Di Stefano and a on-rushing Hassler? Not that I rate Hassler very highly considering who else is around, but he will take away some attention and give all the more freedom for Di Stefano to run the show.

For me, a peak Di Stefano (not the 38 year old one in 1964 when he faced Suarez) would rip Suarez apart.

You always have to remember the context in such games. He might have work rate and defensive capability (not very high as per me and good enough for you which is fair), but do you think that is enough against the giant he is facing? Fair enough if you do.

I am making it tough for myself to pick these players in the future drafts I feel at times

I sort of see that Suarez's defensive game being underrated, but at the same time Di Stefano's attacking game seem really underrated here as well. Don Alfredo made a good point that if it was Maradona in place of Di Stefano, everybody would see harms midfield being sort of inadequate to contain him. I remember in one game I had a midfield of Di Stefano - Matthaus - Neeskens against Maradona and it was consensus that he'll rip us apart as we don't have a bona-fide defensive midfielder. And each of those midfielder is better defensively than Harms midfield.Geez, see that’s the thing which annoys me and people calling (not just you but several others in the thread) Suarez’s defensive ability in question. Put a Xavi or a Falcao there and people probably won’t do that (or not to this extent) but Suarez who has excelled in one of the greatest defensive sides of all time (and not in a Pirlo surrounded by Vidal, Marchisio and Pogba manner) tends to have his defensive credentials questioned more often than not. Fair enough if people think playing in La Grande Inter played a role (once again he played an active defensive role) but seeing his defensive ability for the more expansive Spain in the 1964 Euros or the 1966 WC should make all the difference. Suarez was already an industrious player pre Inter, for both Barca and Spain but it was his move to Inter and tutelage under Herrera that saw him transform his defensive game and further imbue his skill set with defensive nous, positioning and astute ball winning capabilities. As harms pointed out, Suarez wasn’t necessarily a physical hard-tackling midfielder, but a wily and a crafty operator whose reading of the game and positioning meant he made loads of interceptions and his deceptive ability to nick the ball of players resulting in plenty of balls won too.

The thing being for a midfielder of his ilk, he was one of the best defensively in the business, alongside the like of Xavi, Liedholm, Falcao, Overath or Modric (who’d be a good comparison in terms of play style and dynamism). Now will he or any of those midfielders come up trumps against di Stefano, definitely not, and they shouldn’t either as the ‘heavy lifting’ should be done by an accompanying midfielder (Lerby in this case) but will there be any ripping apart? No, I don’t think so.

You don't see the contradictions in logic? My players can't defend one on one but with Tuppet it's somehow one on one battles?I rate Koscis very highly and I don't think Vidic can contain him. Koscis is literally the greatest header of the ball ever, plus countless goals on the ground as well. You would need Vidic to be like the best ever heading CB and a very good one on the ground to contain him completely. Moore has to help out there, he has to help out vs Czibor and he has to help out vs Di Stefano. I mean he is a good fit for that type of role and one of the best CB ever, but he has several open flanks to defend here. Not that your defense will be cut open anytime because you have great last-ditch-defenders and Moore is one of the best around to organize his troops.

Bossis is an okay fit against Figo. Not great but okay. Desailly vs Pele is not great either because there is not one defensive player fit to stop Pele, but could you think of a better one to try it than Marcel Desailly? Fast, strong, great header, equally comfortable in midfield and at central defense (those two areas where Pele is at his best).

McNeill and Beckenbauer vs Law I can buy

You don't see the contradictions in logic? My players can't defend one on one but with Tuppet it's somehow one on one battles?

but at the same time Di Stefano's attacking game seem really underrated here as well.

Wording (rip apart) aside I can totally see Di Stefano getting a lot of freedom in this game. He is as good an attacker as there has ever been. I don't know why I am telling you this as you know more about probably all of my midfield better than me. But anyway I can see anyone going for Harms team, but its almost a fact here that Di Stefano has most freedom of all the players in the game, there is no one containing him and Beckenbauer.

, so don’t mind me. Esp since Suarez was seen as a downgrade defensively to Effenberg, who’s the more physical and hard hitting midfielder defensively but apart from that I’d rate Suarez higher than him defensively. If anything Effenberg’s lack of dynamism or turning pace was more likely to exposed against your di Stefanos and Maradonas than Suarez. If it was “di Stefano’s too much for that midfield duo to handle” or something along those lines, without the exagerrated criticism of both of them here, I wouldn’t have batted an eye.

, so don’t mind me. Esp since Suarez was seen as a downgrade defensively to Effenberg, who’s the more physical and hard hitting midfielder defensively but apart from that I’d rate Suarez higher than him defensively. If anything Effenberg’s lack of dynamism or turning pace was more likely to exposed against your di Stefanos and Maradonas than Suarez. If it was “di Stefano’s too much for that midfield duo to handle” or something along those lines, without the exagerrated criticism of both of them here, I wouldn’t have batted an eye.

I would say it has lost a bit of steel but there was always more than enough of that to start with, with someone like Lerby, but is actually better now defensively. With a steely ball winner like Lefby alongside him, I’d rate Suarez’s defensive nous and dynamism more in this set up.

Ideally di Stefano’s perfect for that role but a more conventional CM there would have made a lot of difference as opposed to Hassler imo, who does require di Stefano to be a tad bit more conservative

Congratulations Harms ! It was always going to be hard against your team. I took some time to decide whether to play Mackay there or Hassler and from what I am reading it seem I chose wrong, although I would have lost with Mackay as well. But my reasoning for picking Hassler was simple. I wanted to attack your 2 man midfield and for that I wanted my midfield to be more proactive. Lerby & Suarez somebody might have bought against only Di Stefano but adding Hassler I wanted to have another outlet for supporting Di Stefano and have a player with similar technical skills as him so they can you know like play 1-2s etc. I would have played Mackay for example if I was against Theon or Onenil where I have to worry about a proper number 10.Good game, @Tuppet. I really liked Desailly's use — hard to imagine a better player to face Pelé, although even that probably wouldn't be enough to contain him.

On the other hand, I was not a fan of Hassler's substitution tbf.

@Tuppet

Perhaps Hassler instead of Bene(who wasn't getting much appreciation) and Mackay in thre central midfield would have been a nice option. Mackay was certainty quite the nifty player on the ball for a B2B and his pass and move/one-two quick tempo playing style would have seen him right at home with Di Stefano.