Heres an article I found today thats worth a read............

From childhood friends to celebrities, Belfast honours its hero

TOM ENGLISH

IN BELFAST

JUST after 12.30pm George Best began his final journey. His coffin, draped in the flag of Northern Ireland, was carried to the doors of the Parliament Buildings at Stormont and down the 60 steps to where the masses gathered. A lone piper played a last lament for a favourite son and this day of days entered its last moments. The funeral cortege inched forward, moving round Lord Carson's statue and down Prince of Wales Avenue, a distance of a mile but one that took an age to complete.

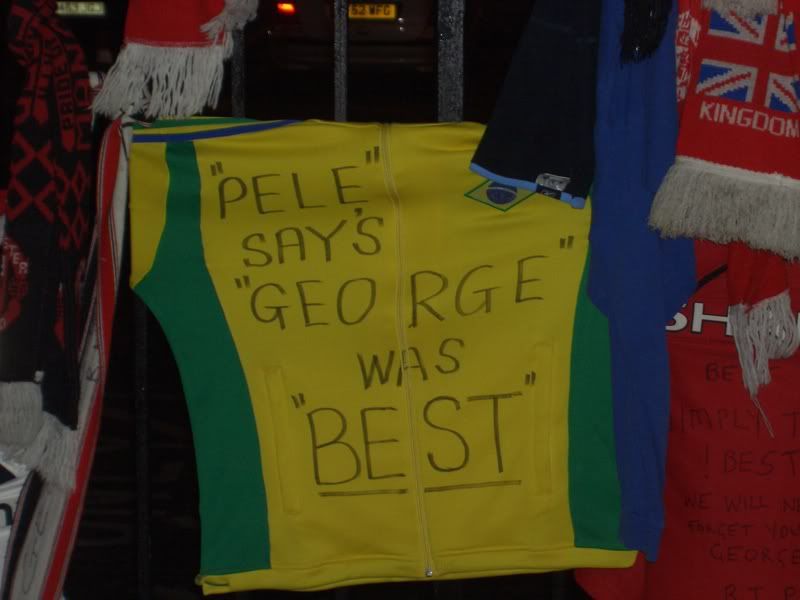

The tributes rained down every inch of the way; all the shirts, flags, scarves and footballs in Belfast were seemingly flung at the hearse as it passed. Flowers came in great numbers and rested on the bonnet. Pictures of Best in his prime were held to the dark skies and there were tears. Plenty of them.

What you noticed most of all, though, was the applause. It began in the grounds of Stormont, continued when the procession made its way on to Upper Newtonards Road and lasted all the way to Roselawn Cemetery where Best was laid to rest beside his mother, Ann.

They arrived from first light, 30,000 people pouring in the gates and tens of thousands more lining the streets outside. Among them, millionaires and paupers, celebrities and has-beens and never-weres. George was at ease in all company, a man whose adoration spanned the great divide in Ulster. Genius can do that. So all sorts paid homage yesterday. People from all communities, from all classes, from all cities and countries. So many had stories to tell.

There is the one about the woman who travelled over from Kilmarnock on Thursday. Imre Rewcastle is writing a book about destiny and said: "George has unfolded into my story over the last few weeks. I had to be here." Just down the line from where the budding author stood there were six likely lads from Manchester looking the worse for wear, Simon Smith the only one among them in a fit state to speak.

The six of them had been drinking in the Northern Ireland football supporters' club in Belfast until three in the morning. Inside, they met Alex Higgins, the untamed genius of the snooker table. Higgins was being himself - drinking and betting and drawing attention. The lads joined him. Before they knew it, it was mid-morning and they had a decision to make. Go back to their digs and get some sleep or start their pilgrimage to Stormont. They walked. Or staggered. Or crawled. But they got there. At about 4am they set up camp outside the giant gates of the Parliament Buildings and waited for them to open. Tired, dishevelled and smelling of booze, Best would have approved, they reckoned.

When the heavens opened around 10am, three sisters huddled together under an umbrella near the giant screen that replayed classic moments from Best's career to a series of poignant soundtracks. Margaret Millan, Sally Thompson and Fay Gogarty had grown up on the same Cregagh estate as Best. Fay knew him well. Truth be told, she fancied him and this formidable lady of east Belfast wasn't shy in telling him.

"We were born the same year, 1946. He was May, I was September. Oh, I loved him, so I did. There was me and Pat Brown and Bell McKeown, God rest her soul. We were a group, about 14 years old at the time. George was so shy as a boy. He always liked his football more than he liked the girls. We'd say 'George, are you gonna walk us home?' He'd go 'aye, sure' but you'd always be standing there waiting. He never did in the end."

As the baby of the family, Margaret is too young to remember her famous neighbour but she had her own tale. One time she happened to be drinking in the same Manchester bar as him. He overheard her talking and came over. "Are you Belfast?" he asked. "Am I Belfast?" she replied. "Not only am I Belfast, George, but I'm Cregagh and you used to hang around with my sister when you were just a skinny wee thing of 14. He was great. He bought us drinks for the night. 'You're Fay's sister! God almighty. Small world, eh?' It was a great night."

Margaret spoke for a lot of people when telling of Best's legacy. "He done more for Northern Ireland than anybody. He always had a smile. He united the communities even in the worst of times. When it was horrible here, really, really dark and when nobody could see a way out, George had a smile for everyone. He'd cheer us up. Catholic or Protestant. Didn't matter. He was just George. Our Georgie Best."

For Sally, the eldest of the three, this was a day of added sadness, of terrible memories of her own past that mirrored the horror of what Dickie Best, George's father, is going through. "I had a son," she says, quietly. "Frankie James Thompson was his name. He was 14. A football nut. You couldn't get the ball away from his feet, so you couldn't. He'd bring it into bed with him. Well, he's buried above in Roselawn, where Ann Best is and where George is going now. This is a very sad day for me. I look at poor George's father and I think of Frankie. No parent should have to bury their child, should they?"

There was much to get emotional about yesterday. The haunting music of Brian Kennedy and Peter Corry, the moving words of Calum Best, his son, Barbara McNarry - George's sister - and Bobby McAlinden, the Scot who became one of Best's closest friends. Recently Calum was sent a poem by a member of the public. It was entitled 'Farewell Our Friend But Not Goodbye'. It moved him so much he decided to read it at the service then broke down midway through.

Barbara McNarry broke down, too. McAlinden soldiered through but you didn't need to see his face to know that the words were a struggle. "He made me his room-mate, team-mate, his partner in a desirable property [when they played football together in America] - he was the greatest friend I ever had."

Big names were everywhere. Sir Alex Ferguson, Sven Goran Eriksson, Martin O'Neill, Denis Law. A celebrity cast of hundreds. But the eye was constantly drawn to Best's father, Dickie. A tiny man in a grey overcoat, the heart went out to him most of all.

Dickie Best has lived in the same modest terraced house on the same working-class estate for the past 50 years. He raised six children, one of whom happened to be the most famous Northern Irishman in history and one of the greatest footballers the world has ever known. But Dickie has had a hard life, harder than most people could imagine.

He's 86 now but still has the hardness of features that comes with a life spent working at the shipyards of Harland & Wolff. But underneath it all, Dickie is a pussycat, a real nice fellow, who passed some of the same human qualities on to his son. Yesterday he buried his boy, 27 years after burying his wife. Drink claimed them both.

Ann Best never touched a drop of alcohol until she was past 40. She died at 54, five years fewer than George managed. "Dickie, I don't want to live any more," she told her husband one October night in 1978. The following morning Dickie brought her up a cup of tea and found her dead in the bed.

It is said that for all these years Dickie has carried some guilt with him about not moving the family to Manchester when he had the chance. At the height of George's fame, Manchester United advised the Best family to move closer to their son, to watch over him and, hopefully, prevent him from falling into some of the traps they could see him heading for.

Dickie declined the offer because by then his wife was drinking hard and he didn't want mother influencing son and son influencing mother. For their own good, they had to be kept apart. It apparently broke his heart, as it would any man.

The old guy was so dignified yesterday that your own heart almost broke. He didn't show much emotion from what we could see, no tears but no smiles either despite Law's best attempts in the first tribute of the day. He told a nice story about the two of them camping overnight at London's Cromwell hospital when Best's health had taken a decisive turn for the worst and he had only hours to live. There was a big couch and a little couch in the waiting room at the Cromwell. Law turned his back for a moment and when he did Dickie hopped cheekily into the larger of the two. "Look at him!" Law said, in a moment of gently mocking humour. "He's the size of nothing."

The 300 invited guests in the Great Hall at Stormont broke into momentary laughter but Dickie didn't join them. You could tell, somehow, that he wanted to. But he didn't.

An hour later they took his boy away. They drove the four miles to Roselawn, the route lined with tributes and applause, and when they reached the burial ground they closed the gates behind them. The Bests, at last, were alone. The most public funeral the province has ever seen - or ever will see - had a private ending. Just Dickie and his family and friends and his Belfast Boy - his fragile, flawed genius of a son who is now gone but who will never, ever be forgotten.