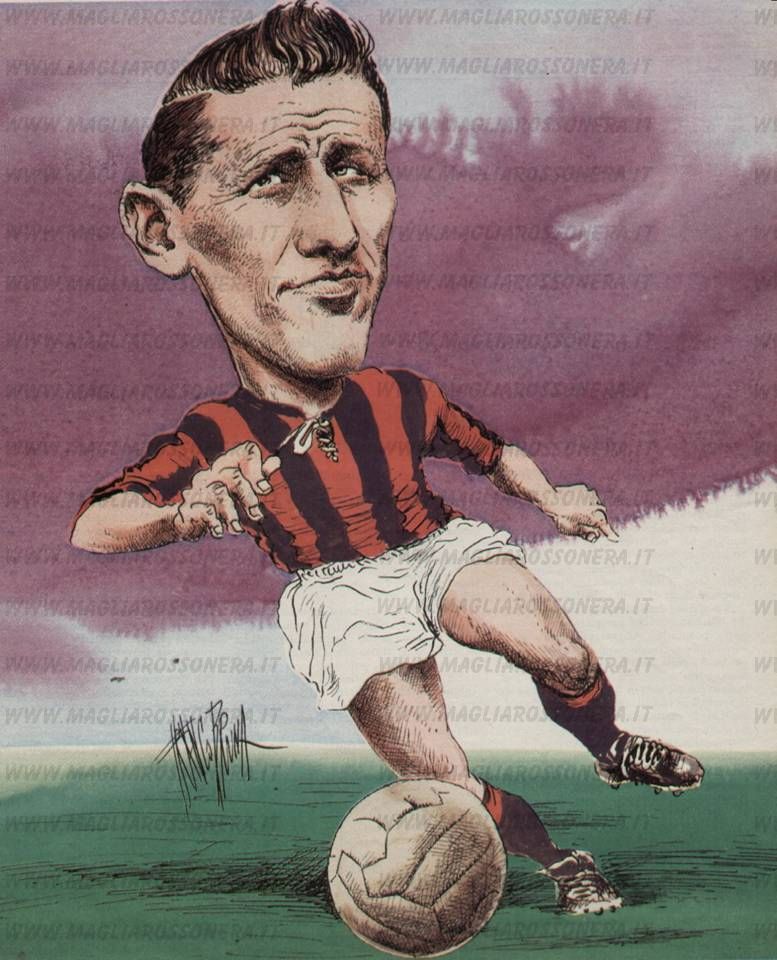

SCHIAFFINO – Il Regista del Diavolo (the Devil's Regista)

“God has reserved the distribution of two or three small things which cannot be attained or countered by all the gold in the hands of the powerful ones:

genius, beauty, happiness". When Gautier wrote these words in 1856 he could not know Juan Alberto Schiaffino, he could not know that this definition would fit perfectly. In the years of Liedholm the number ten is divided between the shoulders of the Baron and those, more slender and graceful, of "Pepe" Schiaffino.

God had given him a gift, a privilege: that of genius. Gianni Brera, still considered the greatest Italian football expert, thought as much:

Gianni Brera said:

There has never been a regista of greater value. Schiaffino seemed to have flashlights in his feet. He illuminated and invented the game with the simplicity that is typical of the great. He had an innate sense of geometry, he found the right position and pass almost by instinct.

Those who had the good fortune of seeing him play remember him, decades later and without a shadow of the slightest doubt, as the best player they have seen. Most of these refer to the final of the European Cup in 1958 as the game that settled it: Di Stefano, Puskas and Schiaffino were all on show and Milan lost 3-2 against Real Madrid, but it was Schiaffino, now thirty-four, who stole the show. Differently from the previous two, he had also won a World Cup, in memorable circumstances. After that game the Brazilian coach had only one thing to say:

"Schiaffino was the unexpected that silenced all our ambition". From that day, Uruguayans had called him “el Dios del Futbol” (the God of Football).

Eduardo Galeano said:

He plays as if he were watching the field from the highest point in the stadium

Cesare Maldini said:

He had a radar for brains

Arrigo Sacchi said:

When I first saw Schiaffino I was 10... I was struck not only by his greatness when in possession of the ball, but also about how he had the property, the capacity, of being everywhere. He seemed to possess the gift of ubiquity

Schiaffino was a universal midfielder, he could do everything and read ahead the development of the game.

He didn’t chase the ball, the ball ran towards him. Which brings us to another characteristic: he was silent, inscrutable but possessed an immense confidence in his own abilities, which often made him a bit stubborn and lippy. He was once suspended for five games after signalling at a ref with his hands that he was on the take, in front of the entire stadium.

He was also the only player known to talk back at captain Varela. The competitive tension between those two was the stuff of legend. One synthesised defensive play, the other synthesised attacking play, so it often resulted in orders/directives being barked in either direction. In 1950, during the final against Brazil and with the game still at 0:0, Varela demanded Schiaffino stopped fannying around the frontline testing defenders and made a more disciplined defensive effort by picking up a certain Brazilian player. “When you can pass the ball to me like I pass the ball to you I’ll take orders on my positioning”, he replied. Then against England in 1954, after Schiaffino moaned about poor service from the centrebacks Varela barked back “Take a woman” (basically, have a shag and chill the feck out).

Of course, there was nothing other than immense respect between the two, with Obdulio having overseen the formation and coming of age of the Death Squad. Schiaffino’s older brother, Raúl (NT and Peñarol forward) brought him to the club aged 16, and he tore up the reserves. As Raúl insisted he should be promoted, Varela argued the opposite: “they are very promising, but

like a good wine we must let them come of age. Juan is ahead of the others, with the seniors he will be behind... and then they will be gone, and he will be alone. Let him stay with that frontline that’s forming around him and bring them all up when they are ready”. The outcome: he got his first cap aged 18, before even playing for Peñarol’s first team, but when he finally got promoted he no longer was a talented skinny little kid. He was boss, and went on to win five national titles and score 88 goals in 227 games.

From an early age he was considered a football intellectual, but one that didn’t only theorise, compute and resolve in an abstract way: he could also execute in practice. He was the tactical and technical conscience of the teams he played for. He was an enemy of football dogmas and conventional wisdom, like the one establishing the forwards should wait for the ball or that anticipation was only a defensive recourse.

He was a pioneer of one-touch play, which better helped exploit the fact he was several seconds ahead of anyone on the pitch. His preeminence was based on his power of discernment, his serene impartiality that allowed him not to get dragged by the urgencies and pressures of the match. He wasn’t affected by temporary adversity, the importance of getting a result, the clock running or the urgency cascading from the stands. A footballing Spartan.

When in 1984 the Italian Federation’s Coversiano Technical Centre consulted the Serie A managers on who had been the greatest foreign player in Serie A all but two responded:

Schiaffino. He left an indelible mark not just through his football, but other innovations he brought about:

1. Brera credits him as the one

introducing the slide tackle in Italy. This must be some translation issue I suppose, it must be some very specific form of slide tackle surely. But he does mention how referees weren’t used to it so erroneously whistled foul.

2. He pushed for changes to how

Milanello was run regarding admission of women and clearly defined schedules for training and resting.

3. Upon joining Roma, aged 35 and without the physical conditioning he used to possess, he applied his intact brain and football intelligence playing between the defence and the goalkeeper: and thus

the role of libero was born. Rumour has it that he was impassable.