POLAND of the 70's and early 80's

On 1 December 1970, Polish football history would change forever all due to one man. Kazimierz Gorski was named head coach of the national team. His success with the team was evident from the start with a gold medal at the 1972 Summer Olympics. Górski would later lead the team to another medal at the 1976 Olympics where they captured silver. However, nothing matched the two bronze medals at the 1974 and 1982 World Cups.

The team here has assembled a few key members of that famed squad.

Kazimierz Deyna

Kazimierz Deyna (23 October 1947 – 1 September 1989) was a Polish footballer, who played as an offensive midfielder in the playmaker role and was one of the most highly regarded players of his generation.

Deyna began playing youth football in 1958 at his local club Włókniarz Starogard Gdański. In 1966 he made one appearance for LKS Lodz. But he was quickly snapped up by Legia Warsaw. In communist Poland each team had its own "sponsor". The Warsaw club was much more powerful as it was the military club. Moreover it was the favourite club of the authorities. Deyna was called up into the army and in this way he had to play for Legia Warsaw. He made a name for himself during his first season, becoming one of Legia's most important players. In 1969 and 1970 his team won the Polish Championship. After his performances at the 1974 World Cup, European top-teams like AS Saint-Etienne, AC Milan, Inter Milan, AS Monaco, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich tried to acquire his services but he was unable to join due to the communist regime in Poland, preventing him from moving to Western-Europe. Real Madrid was so determined to acquire Deyna that they sent a shirt to Warsaw with his name and number "14".

On 24 April 1968, he made his debut for the national team of Poland in a match against Turkey in Chorzow. He won the gold medal in the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, and the bronze in Football World Cup 1976, after a match against Brazil. In 1972 he was also the Top Goalscorer of the Olympic Games, with a total of nine goals. In 1976 Summer Olympics his team yet again reached the finals and won the silver medal. Additionally, he was ranked third in the European Footballer of the Year for 1974, behind Johann Cruyff and Franz Beckenbauer respectively.

Deyna played for Poland on 97 (84 after the deduction of Olympic Football Tournament competition games) occasions, scoring 41 goals, and often captained the side. He had the ability to score from unusual positions, for example directly from a corner. Because of his achievements and talents, he was chosen Football Player of the Year several times by Polish fans. In 1978 he captained Poland at the Football World Cup in Argentina, where the team reached the second phase

Zygmunt Anczok

Born March 14, 1946 in Lubliniec (Katowice province), son of John and Mary Ulfig, a graduate of the Technical Energy (1967) and coaching courses at the Katowice Academy of Physical Education (1981), coach class II. Player (177 cm, 79 kg) - left back, a local graduate of Sparta (1959-1963), the player Polonia Bytom (1963-1971, league), Gornik Zabrze (1971-1974), U.S. clubs in Chicago - the Vistula (1975), Katz Chicago 1975-1976) and the Norwegian Skeid Oslo (1977-1979, and league), as the first Polish player in the country. The Polonia Bytom enjoyed phenomenal success of American Football Cup Interligi (1965) and the Cup Rapp (1965), while playing in Górnik (three league seasons, 38 games) was in one year (1972) Polish champion and winner of the Polish Cup. He was 19 years old when he made his debut in the Polish National Team (1965 in a match against Scotland). He played a total of 48 A + 5 games ending his career in red and white team in the away match against Wales (1973). He was a great defender, playing "a thoroughly modern," ie, that it clung to his position, but moving the entire length of the pitch, often including the action offensive team. Fast, strength marathoner. All these demonstrated advantages, among others. the South American tour, when the famous Maracana in Rio de Janeiro had the attackers rivals such as Pele, Garrincha and Tostao. He confirmed it during the Olympic tournament.

Unfortunately, all too frequent injuries (four metatarsal fractures between the Olympics and World Championships in Munich in the FRG and the two operations meniscus in Oslo) made it did not comment further, the expected success. After retiring Competitive (1979) was a coach in his hometown Lubliniec, and after another illness (this time the pain in the hip, surgery and artificial hip), not being already pełnosprawnym, tried his luck in other professions (business, taxi, shop) until eventually had to retire. Awarded the Distinguished Master of Sports, among others. Gold and Silver Medal for Distinguished Achievement and Athletic Gold Cross of Merit (1972). Player of the year 1966. Together with W. Lubańskim occurred in the FIFA All Star Team (1971), who played for Łużnikach to celebrate the parting of the Soviet football goalkeeper Lev Yashin.

Jerzy Gorgon

Quick quiz: name the greatest non-British central defenders of all time. Go! Done? Good. Franz Beckenbauer plus one of the Italians, right?

A Twitter poll returned Beckenbauer and Franco Baresi as clear favourites, with other Italians nominated including Paolo Maldini, Giuseppe Bergomi,

Fabio Cannavaro, Gaetano Scirea and Alessandro Nesta. Other nominations from across Europe included Marcel Desailly and Lillian Thuram of

France,

Carles Puyol and Fernando Hierro of

Spain, Ronald Koeman and Jaap Stam of the

Netherlands, and the

Republic of Ireland's Paul McGrath. Argentines Roberto Ayala and Daniel Passarella also featured. The usual lot, in other words, along with Pascal Cygan, Jose Fonte, Steve Gohouri, William Prunier, Efe Sodje,

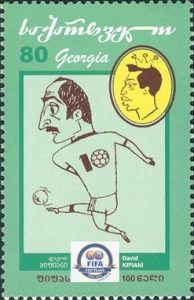

William Gallas, and Zurab Khizanisvili, because people on the internet are hilarious.

Nobody, however, voted for 6'4" Polish stopper Jerzy Gorgon. This is because Kevin Keegan isn't on Twitter.

Gorgon -- a

pretty scary-looking mother -- played most of his career for Górnik Zabrze between 1967 and 1980. He was part of the team that won five straight Polish Cups between 1968 and 1972, and as well as winning a couple of titles they reached the quarter-finals of the European Cup in 1968, and lost to Manchester City in the final of the 1970 UEFA Cup. Internationally, he played 55 times for Poland and won gold in the 1972 Olympics, and silver four years later. He was also part of the side that finished third in the 1974 World Cup.

Anyway, Gorgon doesn't have much to do with the game any more; he lives in

Switzerland, he is an ambassador for Górnik, and he inaccurately predicted that Poland would easily beat England in their recent rain-delayed World Cup qualifier. However, way back in 1979, Kevin Keegan decided that he was just the man to partner Beckenbauer in his Greatest Not British XI of All-Time.

Keegan, as English footballers are wont to do, had decided to alleviate the tedium of being a professional by writing himself a book. Written with the

Sunday People's Mike Langley,

Kevin Keegan -- Against the World isn't quite the usual account of ‘what I did on my incredibly expensive holidays'. Chapter 2, for example, is called ‘The Decline of England', and opens rather wonderfully: "I danced in a Doncaster pub-disco one summer evening nine years ago neither knowing or caring that, thousands of miles away, Bobby Charlton's champagne had gone flat."

Having dealt with the failures of his nation and delivered his thoughts on Don Revie, goalkeepers, supporters and

Germany, Keegan goes on to select his Greatest XI's -- one British, one Others -- to face off in the Keegan Cup. Of those Forriners, Keegan wrote "The team is packed with scorers," and he wasn't kidding: his four-man front-line reads Pelé, Johan Cruyff, Gerd Müller and Mario Kempes. Behind them he picked Brazilian genius Rivelino and AC Milan attack-dog Romeo Benetti, as thunderingly-moustachioed a midfield as was ever conceived. The full-backs were Giacinto Facchetti and Berti Vogts, who apparently used to be a footballer before he became a Scottish figure of fun. Sweeper was Franz Beckenbauer, and alongside him, winning the ball for the Kaiser to use, Gorgon.

Keegan's own explanation for his choice isn't particularly illuminating. Where Beckenbauer gets four paragraphs, an anecdote, and a healthy dollop of awe -- "Beckenbauer is not normal; he could see, or perhaps sense, everything behind me" -- his notes on Gorgon's entry read, in their entirety:

Jerzy Gorgon of Poland is my centre-half. ‘A donkey' was Brian Clough's assessment, but I think that Gorgon copes most effectively with his technical limitations. He is a strong stopper with some skill and would balance with my sweeper, who is best partnered by a big man willing to attack the ball.

Faint praise, they call that. While many of the traditional pantheon of All Time Great central defenders -- see that list above -- were yet to come. Even looking for a man to play alongside a sweeper, it's an interesting call to pick the big Pole ahead of, say, Scirea's club partner Claudio Gentile. Even more intriguingly, it doesn't appear that Keegan ever played against Gorgon.

Michał Zachodny, co-editor of

Ekstraklasa magazine, suspects that Gorgon's style -- "similar to English defenders of the time" -- may have played a part in Keegan's choice. "He was a hard-tackling, fine-heading, long-punting central defender with a good turn. Apparently his opponents were simply scared of him." Zachodny also points out that Gorgon bumped up against English opposition on two notable occasions: the aforementioned UEFA Cup final, and playing for Poland in qualification for the 1974 World Cup.

England were expected to qualify easily from a three-team group comprising the Poles and Wales, but the first game, away in Chorzow, ended 2-0 to Poland as Gorgon and company defended stoutly and took advantage of a sloppy performance from Bobby Moore. Then, for the notorious Wembley return, Moore was dropped by Alf Ramsey. The match itself, a 1-1 draw, is part of footballing folklore -- here's Brian Clough calling Jan Tomaszewski a clown, there's Norman Hunter giving the ball away for Poland's goal -- though the nostalgic clip shows tend to elide Martin Peters's post-match confession that

England's equalising penalty might not have been wholly warranted. "He barely touched me but I went flying. I dived. It wasn't a penalty, but the referee didn't see it that way". He, of course, was Jerzy Gorgon, who later recalled:

Fans and players were screaming 'animals' at us and it could break few with not as strong mentality as ours. Even though we were knackered after game with Cardiff, they were kicking us much harder than the Welsh team. We knew what to expect though. After the game they didn't even want to shake our hands.

Those qualifying games occupy a deeply sensitive place in the collective memory of English football: it was the first time the national team had failed to qualify for the World Cup since they'd deigned to grace FIFA with their presence, and it was the end of both Moore and Alf Ramsey, icon and overseer of the 1966 triumph. Keegan had made his debut in first game against

Wales (Wales 0-1 England, described by Ramsey as "Neither exciting nor entertaining") and also played in the second (1-1, England booed off at Wembley), but missed both matches against Poland. His book is sadly silent on whether he spent the time watching the games, or in a bingo hall in Darlington, but you can see why the defensive heart of the team might have made an impression.

Back to the question of the all-time best centre-back. It's odd that the recollections of footballers often vary from the wider, accepted pantheon. Gorgon isn't the only player along these lines to have been lauded by his certain of his peers but neglected by history. Pietro Vierchowod, an Italian defender of Ukrainian descent, was named by both

Gary Lineker and Diego

Maradona as their toughest opponent. Linker described him as "brutal and lightning quick", while Maradona said "He was an animal, he had muscles up to his eyelashes". Yet he's another name generally missing from the conversation.

Obviously, elite footballers have knowledge not available to mere mortals: professional expertise, personal respect (or contempt), understanding of what the whole business involves, and so on and so forth. Doing something gives you a perspective on that thing that outsiders don't have. This doesn't make their views necessarily better or right -- there's more to it than that, and there are plenty of thick footballers -- and it certainly doesn't justify Alan Shearer, Pundit-at-Large, but it does mean they may approach a question from a different angle and arrive at a different conclusion. That's why so much time is spent interviewing them: the hope of insight. An entertaining recent example of this was provided by

Carlos Tevez, who was asked, as one of the few people have been teammates of both

Lionel Messi and

Cristiano Ronaldo, who he considered the best he'd played with.

Paul Scholes, he replied.

Even more generally, we might perhaps acknowledge that the pantheon is perhaps not quite as rigorous as we might like to assume. Entry depends not just on talent, or even what a player does with that talent, but also where he does it, how he does it, who he does it with, and what notice everybody else takes. Fashions come and go, and players are lost to the tides of history. If a footballer wins a trophy in Poland in the 1970s, and only Kevin Keegan is watching, does he make a sound?

Maybe, in another universe, Jerzinho Gorgonzola's mound of domestic and international silverware sees him estimated alongside Beckenbauer by the world at large, not just by a former England striker trying to pad out his book. Maybe footballing greatness is, at heart, an uncertain exercise dominated by luck, circumstance, and imperfection to a far greater extent than those of us who like telling stories about it would ever care to admit. As Gorgon's international coach Kazimierz Górski put it: "You can play football for 20 years and play 1,000 times for the national team and nobody will remember you."

- 23.01 Monday

- 23.01 Monday

- 23.01 Monday

- 23.01 Monday

- 23.01 Monday

avid BECKHAM 1998-2002 & 2003-2005 , Josep GUARDIOLA, Luis SUAREZ, Günter NETZER, Dragan DŽAJIĆ