Nowadays the term ‘fair play’ has degenerated into kicking the ball out of the pitch when a player is faking an injury while the spectators award the players on the pitch with shallow applause that holds no real meaning. While fair play has slowly turned into an empty gesture – a leftover from a simpler time where money and winning wasn’t everything – it hasn’t always been like that.

One of the best tales about fair play is from the 1962 World Cup. After beating Yugoslavia and drawing against Colombia in the first two games, the Soviet Union were forced to beat Uruguay in the last game of the group stage in order to advance. And things started well for

Sbornaya as CDKA Moscow striker Aleksei Mamykin secured the lead with a goal in the first half. Uruguay equalised in the second half, and the pressure was back on the Soviet team to score the winning goal.

In the second half the Soviet players and fans got to celebrate as Dinamo Moscow striker Igor Chislenko brought

Sbornaya back in front. However, Igor Netto, the Soviet captain, had noted that something was wrong, and after a short chat with Chislenko he approached the referee, who was surrounded by protesting opponents, and told him to disallow the goal, which he did, because the ball went through a hole in the side netting, something the Uruguay players had also noticed.

“We weren’t used to the gimmicks,” he later recalled in his autobiography. And luckily for Netto and the rest of the Soviet Union, they didn’t need any gimmicks to win the game, as legendary Torpedo Moscow striker Valentin Ivanov scored the winning goal in the 89th minute. “We should win without relying on the referee’s mistake. I finally felt a sense of relief,” Netto recalled the game.

In 1962, Netto’s career was at a high, and the episode at the World Cup tells a lot about the man who went down in history as one of the greatest players, not only for Spartak Moscow, but also for the whole Soviet Union and later Russia.

Despite dying in 1999, Netto is still remembered and often honoured by both Spartak and Russian fans as a whole. Before Russia’s Euro 2016 qualifier in Moscow against Sweden last year, a giant tifo with the faces of Netto alongside Lev Yashin,

Eduard Streltsov and Grigory Fedotov was shown together with the words: “Take pride in your history”.

The year before,

Spartak fans had done something similar when they pictured Netto alongside Nikolai Starostin, Fedor Cherenkov and Andrey Tikhonov with the words: “Be worthy of the great history”.

Netto does indeed have a great history. Born into an immigrant family of Estonian decent in 1930, the young Netto quickly showed promise of great athleticism. He would spend summer hours playing football with his mates. Due to the lack of proper pitches and grass fields in Moscow, the boys played in the small yards around the city, a game later known as korobka, and it helped create strong technical players who were comfortable playing in small areas surrounded by opponents. As the winter came, the technically gifted Netto changed to skates as he, like most other Soviet citizens, also enjoyed playing ice hockey.

Igor Netto

As Netto grew older it became clear that the beautiful game of football was his true love, and where his future lied, but he could never quite leave the game of ice hockey, and even after he became a regular in Spartak’s first team, he made several appearances in the best Soviet league; indeed, after he retired from football in 1966, he worked as an ice hockey coach for a while before eventually returning to football.

At the age of 19, Netto was discovered by Spartak who gave him the number 6 and immediately made him a part of the first team. The Red-Whites were in the middle of one of the worst periods in the history of the club, and they hadn’t won the league in 10 years by then. They had also lost most of their pre-war regulars to local rivals Dinamo and CDKA, who took advantage of Spartak’s poor health, while the club founders, the four Starostin brothers, were imprisoned in a Gulag.

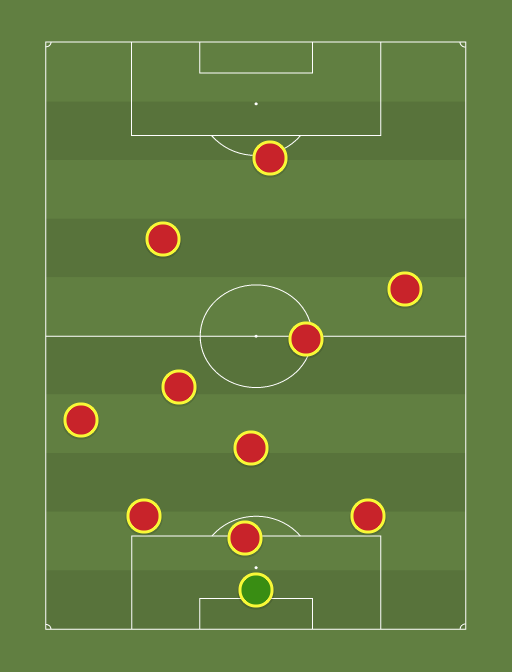

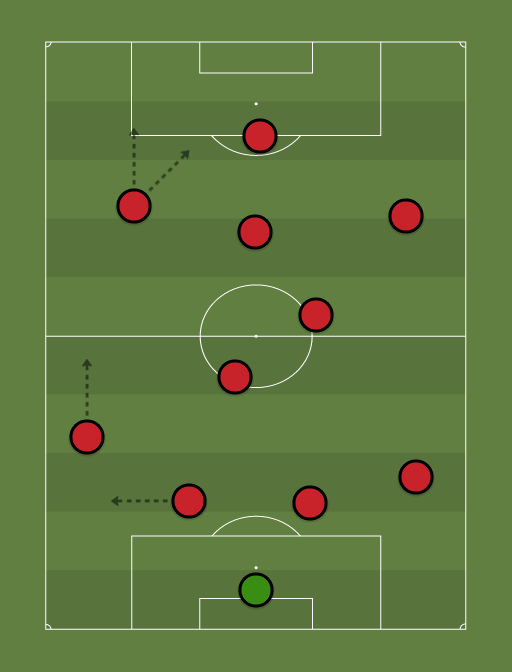

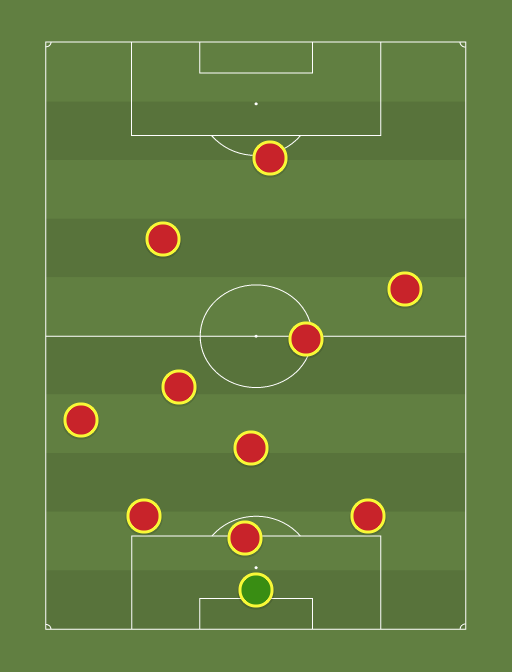

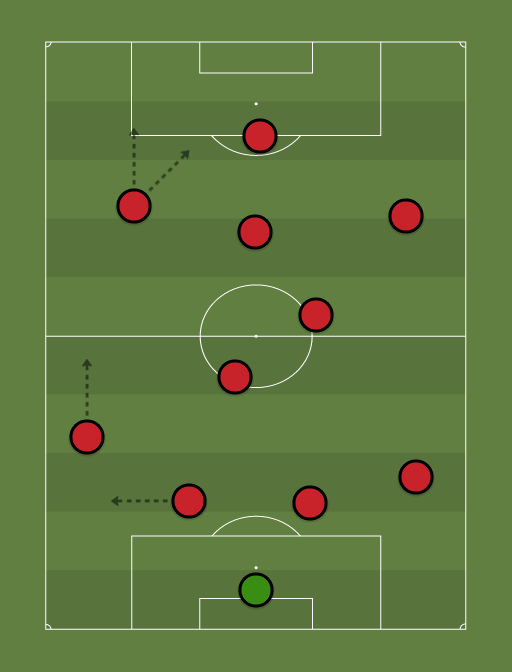

They were therefore in need of young players with whom they could build a new powerful squad around, and Netto fitted perfectly into this plan. Just like many great Spartak players before and after him, he both preferred and mastered a possession-based approach to football. Initially he started in defence, but soon after head coach Abram Dangulov figured out that he could utilise his strong passing skills, incredible vision of the game and great technique better further up the pitch, Netto was moved to midfield, where he developed into one of the finest box-to-box midfielders in history.

“Igor Netto was definitely a player ahead of his time,” Joel Amorim, Spartak Moscow expert at

Russian Football News says. “He was too talented to play on the left side of the defence or even as a wide midfielder, but he still turned out to be one of the most brilliant playmakers of all-time. He had a golden left foot and you still cannot find many players these days with his passing skills and incredible vision.”

Dangulov was appointed head coach of Spartak in 1949 after Krylya Sovetov Moscow was disbanded the year before, and with him he brought one of the most promising young strikers in the country,

Nikita Simonyan. Simonyan went on to become the highest scoring player in the history of Spartak, and with those two in the team, the Red-Whites started their trip back to the top.

In Robert Edelman’s book

Spartak Moscow – The History of the People’s Team in the Worker’s StateSimonyan explains Netto’s approach to football: “He [Netto] completely refused to recognise that there was such a thing as a long pass. He was very self-confident and never wanted to make a mistake with a pass. He never took a risk, and if any of us made a long pass, he would shout: ‘What’s with you? Are you playing village football?’”

“After the World War, Spartak had big problems,” Konstantin Evgrafov, Editor-in-Chief at

Euro-football.ru and a Spartak supporter explains. “But then some young players began to come into the first team, one of them being Netto, and slowly Spartak started to work their way back to the top of the league.”

By 1952, the former Spartak defender Vasily Solokov had replaced Dangulov and the gamble on the young players was finally paying off as Spartak secured their first league title since 1939.

Igor Netto and Lev Yashin

That was also the year when Netto received his debut for the national team as he took part in the Summer Olympics in Helsinki, where he started in the legendary 5-5 draw against Yugoslavia in the First Round.

Sbornaya were down 5-1 after 60 minutes, but late goals from Vsevolod Bobrov, Vasily Trofimov and Aleksandr Petrov brought the Soviets back into the game and forced a rematch that was due to be played two days later.

The match had serious consequences for the Soviet players as it was played just a few years after Yugoslavian president Josip Tito refused to submit to Joseph Stalin’s interpretation of communism, which made the result personally important to Stalin – who wasn’t normally fan of football – as he couldn’t tolerate a defeat against the man and country who had defied him.

His anger was known to the players when the Soviet team lost the rematch 3-1, despite leading through an early goal from Bobrov. Head coach Boris Arkadiev was stripped of his Merited Master of Sports of the USSR title, and CDKA Moscow, the side that had delivered the backbone of the squad, was temporary disbanded.

After the initial disappointment, the following years turned out to be more successful for Netto and the national team.

He captained the team when they won the 1956 Olympics in

Melbourne. Playing in his preferred number six role, Netto started all five games on the road to the title, and with the exception of a dreadful 0-0 draw against Indonesia in the opening game,

Sbornaya won all of their games on the road to the title.

Three years before the final Stalin had died, and so the pressure was somewhat reduced this time. The Soviet Union won 1-0 after a goal by fellow Spartak player Anatoliy Ilin. The year after, Netto and his team-mates were all awarded the prestigious Order of Lenin for their contribution to Soviet sport, which was the highest decoration in the Soviet Union.

While his friends and team-mates were celebrating the victory on the long trip home from Australia, Netto received terrible news from home that his father had died. Unwilling to ruin his team-mates’ celebrations, Netto didn’t reveal this to anyone until they got back.

Netto was also the captain when the Soviet Union participated in the first edition of the European Championship four years later, the so-called European Nations’ Cup.

Alongside players such as Dinamo Moscow goalkeeper

Lev Yashin and Torpedo Moscow striker Valentin Ivanov, Netto captained what is believed to be the Golden Generation of the Soviet Union at the tournament that was played in France.

Read |

Read | Lev Yashin: the heroic gentleman in black

With only four teams participating, they started in the semi-finals, where the Soviet Union demolished Czechoslovakia 3-0 after two goals from Ivanov and one from his striking partner Viktor Poneldenik. In the final at the Parc des Princes in Paris, Yugoslavia awaited them once again.

Netto started both matches and helped the Soviet Union beat their Eastern rivals 2-1 in the final after Poneldenik scored the decisive goal in the 113th minute of extra time. Being the captain, Netto was one of the key forces behind the victory, which was taken note of around world. It was even rumoured that the mighty Real Madrid pursued him in the summer of 1960.

However, history hasn’t been kind to Netto, and he is rarely remembered outside of the now former Soviet Union. “Lev Yashin’s enormous talent helped people forget Netto,” Amorim says. “But he wasn’t by any means any less important to the Soviet Union national team than his iconic team-mate.”

The men in charge of Soviet football knew that. “Igor’s impact on the other players was great,” Spartak boss

Nikolai Starostin later said. “It was no coincidence that, despite his young age, the players chose him as captain of Spartak, although there were other candidates who were more experienced. Soon after, Netto became captain of the national team and it was no surprise that during this time the USSR had two of the greatest successes in its history: becoming Olympic champions and European champions.”

Netto was 30 when the Soviet national team won the European championship, and looking back it was his peak. In the last six years before retiring from Spartak and the national team, he went on to win just one more national championship and a domestic cup.

When he retired in 1966, he could look back on a career that lasted 18 years in which he had represented Spartak in all of them. “He is one of the biggest legends of the club, which his 18 seasons, 368 matches and 36 goals for Spartak proves,” Spartak supporter Vincent Tanguy of

Russian Football News says. “For me, only Fedor Cherenkov and Nikita Simonyan are on his level.”

“Igor Netto and Fedor Cherenkov are, as far as I’m concerned, the most important players in Spartak Moscow’s history due to their attitude on and off the football pitch,” Amorim adds.

And as proven by the disallowed goal in 1962, Netto’s attitude off of the pitch was partly what made him unique. In fact, he can be described as the personification of a famous Spartak idiom originally coined by Andrei Starostin: “Everything is lost except honour.”