English football in the 1990s was at a crossroads for many reasons. At the club level, the transition from the old First Division into the other-worldly Premier League was in full swing with domestic players predominantly being moved aside for younger, flashier and outright better footballers. Gone were the days of hefty, immobile target men who held the ball up and proceeded to use their elbows in the same manner a boxer used their firsts. In came the sophisticated foreigners, with their sophisticated tactics, who in turn added a whole new dimension to the game in England.

At international level, England were transitioning out of the Bobby Robson era into the Graham Taylor one, then to the Terry Venables era and finally to Glenn Hoddle’s. Four managers, three World Cups and two European Championships in the 1990s, and while turnover of talent may have been a common thing in both the Premier League and at England, there was one player whose talents may have been lost to the decade, hidden behind the overseas imports and bigger names. This particular player spent the entirety of his 90s Premier League career at one club and played for all but two of England’s managers during the decade. Yet he is almost exclusively remembered for one thing: injuries.

Darren Anderton is one of a select group of players who will always be associated with the 90s; his curtain hairstyle, long-sleeved tops in all weather, Pony shirts with Holsten emblazoned across the midriff, tricky attackers who brushed shoulders with the likes of Jürgen Klinsmann and Paul Gascoigne. Alas, there was far more to the man than cheery anachronisms and nostalgic throwbacks.

Some may not remember Anderton’s start to life at Spurs, in which he was predominantly deployed in a frontline alongside Teddy Sheringham and Nick Barmby, but so impressive were his performances, Anderton became a fixture in Venables’ England squads. So good were his performances for England, Manchester United became interested in acquiring his services, thanks to Gary Pallister, who handed Anderton’s phone number over to Sir Alex Ferguson.

Ferguson and United were made aware of a release clause in Anderton’s contract and tried to sign him from Tottenham, but with Klinsmann, Barmby and Gheorghe Popescu all departing, Tottenham boss Alan Sugar was determined to keep his only star asset at the time and refused to let Anderton leave. Anderton signed a new contract, dismantling the aforementioned release clause, and in the process batted away the affections of Manchester United.

In the 1995/96 season, Anderton missed most of the Premier League campaign through injury, however he did make England’s Euro 96 squad, playing a big role in their historic road to the semi-final. Although history remembers it differently, he could have played an even bigger role. When you mention that fated semi against Germany, people will always remember that Gascoigne miss. They remember his blonde hair on the turf, the tears, but what they fail to recall is that England hit the post earlier in extra time. To be more precise, Anderton hit the post.

Had he scored the goal to defeat Germany, to send his country through to the final, he would’ve been the hero of the nation but, as it always seemed to work out for him, he couldn’t quite get the final piece of the jigsaw to fit. Football came home that summer, although only fleetingly, and Anderton always counts it as the most exciting time of his career. In the following 1997/98 campaign, it was back to the same old story as injuries curtailed his season, though he did make the World Cup 1998 squad, this time under Glenn Hoddle.

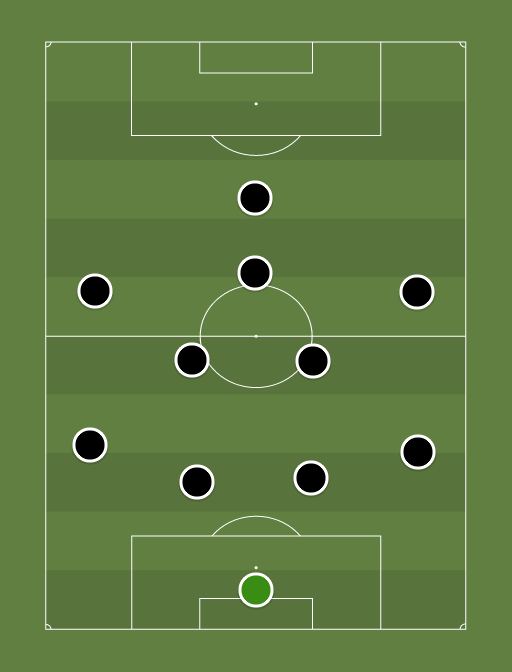

In 1996, Anderton was a player that Venables could rely on, and in 1998, Anderton was a player that Hoddle could rely on. For the first two games of the tournament, Hoddle did as Anderton played in place of David Beckham on the right wing, Hoddle feeling that Anderton was a better defender and was just as good at crossing.

The two did eventually play together against Colombia in the knockout round (both scoring, incidentally) and it stood as a testament for Anderton’s mentality that he was relied on by two managers who had other players at their disposal. Anderton would always give 100%, he would always be creative and industrious simultaneously and would always be there to pop up with a goal, assist or create a chance whenever it was needed. Splitting his role between an attacking midfielder and as a right-winger with a boot that occasionally switched from wand to hammer.

Go, watch some of his goals back, he had some bullets mixed in between goals that wouldn’t look out of place had they been scored by his Tottenham teammate, Klinsmann. His experience through the middle made him clinical when bearing down on goal, and even when playing in Spurs squads littered with classic footballers of the decade, such as Darren Caskey, Stuart Nethercott, Jason Dozzell, Ruel Fox, David Kerslake, Anderton still found a way to stand out.

You don’t come as close to a move to Manchester United as he did without good reason, just as you don’t play for England 30 times without one too. It’s a mighty shame that Anderton’s qualities have since been forgotten or, at the very least, been strong-armed to one side, as the defining memory of Anderton’s career became one of a plague of injuries above all else. The point remains, when Anderton wasn’t injured, he was top class. He could have played for almost every Premier League team and he certainly had the qualities to make any squad significantly better. When one manager trusts you in their line up, it’s proof a good relationship. But when multiple revered managers select you, always placing their trust in you and your ability, that speaks volumes about your talent and your qualities.

Even during the Christian Gross era at Spurs, when pushed out of the right-midfield position by Allan Nielsen, Anderton still found a way to be useful from off the bench. Teddy Sheringham took the limelight for a lot of stellar Tottenham seasons, and rightly so, but Anderton was always there to provide him chances. Jürgen Klinsmann took the goalscoring mantle off of Sheringham when the latter departed for Manchester United, yet Anderton did the same thing with Klinsmann, and again for David Ginola and Les Ferdinand, albeit in a lesser role. In 1999, Spurs’ League Cup-winning season, only Sol Campbell and Stephen Carr played more games throughout the season than Anderton.

Despite being a player remembered for his fragility, and being as stereotypical a 90s Premier League footballer as any, Darren Anderton reached the semi-finals of a European Championship on home soil; played at a World Cup; reached 30 caps for England; won the League Cup in 1999, and performed consistently in the Premier League for an entire decade, alongside legends of the division in the form of Sheringham, Klinsmann, Ferdinand, and Ginola.

If that is to be looked back upon as a bad career, then we may as well pack it all in and go home. Darren Anderton should be remembered for his professionalism and substantial qualities on the pitch, not the habits of unfortunate injuries that so agonisingly kept him off it.