Karl Malden, Everyman Actor, Dies at 97

Karl Malden, the Academy Award-winning character actor whose half-century in show business carried him from the theater to films and then to television, where he policed the streets of San Francisco and became indelibly identified with a commercial for traveler’s checks, died Wednesday at his home in Los Angeles. He was 97.

In many ways, Mr. Malden was the ideal Everyman. He realized early on that he lacked the physical attributes of a leading man; he often joked about his blunt features, particularly his crooked, bulbous nose, which he had broken several times while playing basketball in school. But he was determined “to be No. 1 in the No. 2 parts I was destined to get,” he once said.

He wound up playing everything from a whiskey-swigging cowboy to a prison warden, from an Army drill sergeant to a combative priest.

On Broadway, he appeared with Marlon Brando in a legendary production of Tennessee Williams’s “Streetcar Named Desire,” then repeated the role in a film version that brought him an Oscar. On film he won memorable parts in major productions like “On the Waterfront,” “Ruby Gentry” and “Patton.”

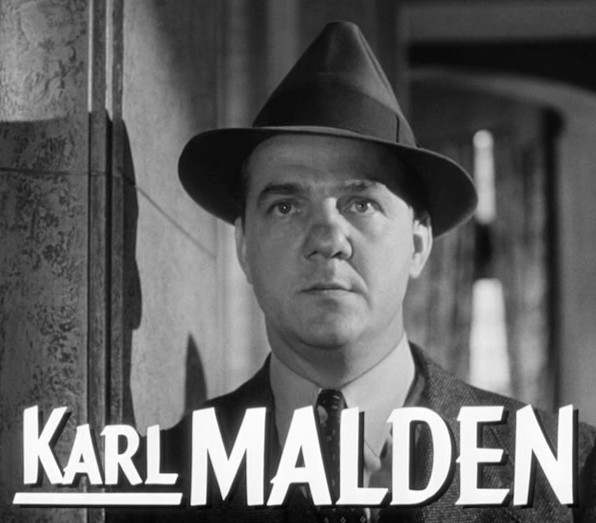

And on television he found broad popularity as Lt. Mike Stone in “The Streets of San Francisco” and as a long-running pitchman for American Express travelers’ checks in the 1970s. His signature line, “Don’t leave home without them” — delivered as he peered intently from under the brim of his “San Francisco” fedora — entered the popular lexicon as a catch phrase.

Mr. Malden’s Broadway career began in 1937 with a small part in Clifford Odets’s “Golden Boy,” a drama about a doomed prizefighter, and reached its peak a decade later, in 1947, when he appeared in two major plays, both directed by Elia Kazan.

He began the year in “All My Sons,” Arthur Miller’s searing drama about a profiteering manufacturer (played by Ed Begley) who sells faulty parts to the Army during World War II and then pins the blame on his partner. Mr. Malden played the partner’s disillusioned son. It was an auspicious debut for Mr. Miller as well as a triumph for Mr. Kazan and the cast.

A few months later, Mr. Malden won a plum role in “Streetcar Named Desire.” The production made a star of Mr. Brando, who created the role of the brooding, hard-drinking mechanic, Stanley Kowalski. The cast also included Kim Hunter as Stella, his long-suffering wife, and Jessica Tandy as Stella’s fragile, haunted sister, Blanche du Bois. Mr. Malden played Mitch, Blanche’s hopelessly inept suitor.

The play, director and cast won raves from the critics, and Mr. Malden, Mr. Brando and Ms. Hunter repeated their roles in the 1951 film version, also directed by Mr. Kazan, with Vivien Leigh as Blanche. Mr. Malden’s performance brought him an Academy Award as best supporting actor.

Three years later, he received an Oscar nomination for his role as a militant priest in Budd Schulberg’s bloody drama of dockside brutality, “On the Waterfront.” Here again the director was Mr. Kazan and the star was Mr. Brando, as a battered former prizefighter who is persuaded to oppose the venal leadership of the longshoremen’s union.

Mr. Malden returned to the stage in revivals of Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt,” with John Garfield and Mildred Dunnock, and Eugene O’Neill’s “Desire Under the Elms,” in which he starred as the flinty patriarch of a hardscrabble New England farm.

In 1957 he played the title role in “The Egghead,” a drama by Mr. Kazan’s wife, Molly, about a liberal professor who defends a former student charged with Communist sympathies. Brooks Atkinson, writing in The New York Times, was cool to what he saw as a strained thesis play, but he lauded “one of those excellent Malden performances in which thoughtful timing, the poised stance, the inquiring look into the faces of other actors yield a winning impression of homeliness and sincerity.”

When “The Egghead” closed after only 21 performances, Mr. Malden turned to films. For a while, he shuttled between New York and Hollywood, but finally, after co-starring with Mr. Brando in the 1961 western “One-Eyed Jacks,” he bought a house in Los Angeles and moved west with his wife, Mona, and two daughters, Mila and Carla.

His wife, of 70 years, and daughters survive him, as do three grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

Mr. Malden was born Mladen Sekulovich in Chicago on March 22, 1912, one of three sons of Petar Sekulovich, a Serbian immigrant who worked in a steel mill and later delivered milk, and the former Minnie Sebera, who came from Bohemia, later to become part of Czechoslovakia. As a young man, Mladen helped his father deliver milk in Gary, Ind., and spent three years working in the same mill.

At 22, having acquired a taste for the theater and determined to make his own life far from the mills, he set off for Chicago with a few hundred dollars in savings to study acting at the Goodman Theater. He earned tuition by building sets and eventually met the woman he would marry, an aspiring actress named Mona Greenberg.

He graduated from the Goodman in 1937 but found himself back in Gary driving a milk delivery truck, much as his father had. Luck came along in a letter from Robert Ardrey, a playwright he had met at the Goodman. Ardrey invited him to New York to try out for a part in his latest play. The play was never produced, but Mr. Malden also auditioned for the director Harold Clurman and Mr. Kazan, who were casting “Golden Boy” for the Group Theater. He wound up with “four lines in the third act,” he later wrote, but it was a significant initiation.

The Group Theater and “Golden Boy” began a half-century friendship between Mr. Malden and Mr. Kazan. It was Mr. Kazan, in fact, who persuaded the young actor to change his baptismal name to something less daunting. So Mladen became Malden, and he took the name Karl from one of his grandfathers.

He also took classes with the Group Theater in the early 1940s and later with the Actors Studio, but he did not regard himself as one of the studio’s Method actors. “I do have a method, of course,” he wrote in his 1997 autobiography, “When Do I Start?” He said it was “any method that works.”

After serving in the Army in World War II, Mr. Malden played a drunken sailor in a Clurman and Kazan production of Maxwell Anderson’s 1946 play “Truckline Cafe.”

The play was a flop, but Mr. Malden got good notices. The reviews also took note of another young actor who had made the most of a small role: Mr. Brando. The two actors became friends, and little more than a year later, they and Mr. Kazan collaborated on “Streetcar.”

After his Oscar-winning performance in “Streetcar,” Mr. Malden became one of Hollywood’s leading character actors, appearing as the wealthy man Jennifer Jones marries to spite Charlton Heston in “Ruby Gentry” (1952); the policeman in Alfred Hitchcock’s “I Confess” (1953); the slow-witted husband of a child bride in “Baby Doll” (1956), another Tennessee Williams story directed by Mr. Kazan; and the domineering father of Anthony Perkins in the baseball drama “Fear Strikes Out” (1957).

With his movie career tailing off in the early 1970s, Mr. Malden reluctantly tried his hand at television. “I felt that I had started at the bottom in the theater and worked my way up for 20 years, then started at the bottom with bit parts in films and worked my way up for another 20 years,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I didn’t feel like starting at the bottom again.”

Nevertheless, he agreed to star in a new detective series on ABC, “The Streets of San Francisco,” in which he played Lt. Mike Stone, a veteran detective. Making its debut in 1972, it was an immediate hit and ran through June 1977. Mr. Malden’s sidekick was Michael Douglas, who left the show in 1976. It was a new world for Mr. Malden. “I had no illusions about creating great art,” he wrote.

He appeared in a few more movies in the 1980s, notably as the stepfather of Barbra Streisand’s call girl in Martin Ritt’s film “Nuts.” There were television shows, including the 1980 NBC series “Skag,” in which he reached back to his roots to play a hard-bitten foreman in a steel mill. In the 1984 NBC drama “Fatal Vision,” he played a man who belatedly realizes that his son-in-law is a murderer. His performance brought him an Emmy award.

In one of his last appearances, in “The Hijacking of the Achille Lauro,” a 1989 made-for-television movie, he was cast as Leon Klinghoffer, the passenger on a Mediterranean cruise ship who was murdered by Palestinian terrorists.In 1989, Mr. Malden became president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the organization responsible for the Academy Awards. He served in that post for three years.

In 1999, he urged the academy’s board to award an honorary Oscar to his old friend and mentor Elia Kazan — an honor bitterly opposed by those who never forgave Mr. Kazan for testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952 and informing on colleagues who had been members of the Communist Party.

“If anyone deserved this honorary award because of his talent and body of work,” Mr. Malden said in an interview after the board voted its approval, “it was Kazan.”

Mr. Malden never forgot his beginnings as a son of immigrants, nor did he lose his perspective. Not long after his work with Vivien Leigh in “Streetcar,” he referred to himself as probably “the only ex-milkman Vivien ever kissed in a movie.”

In an interview nearly a half-century later, he said he thought of an actor’s work as “digging ditches.”

“Sometimes they’re deep and sometimes they’re shallow,” he said, “but we keep digging them.”